IMD business school for management and leadership courses

A New Way of Thinking About Growth Beyond Scale

An earlier version of this article is published by Channel News Asia

If there’s a shifting target for the world, it’s when we can enjoy the post-coronavirus era. Every time we see a glimmer of hope, another variant comes along, hitting another region and causing some more disruption of the global supply chain.

It’s a recurring nightmare that exhausts everyone.

By the second half of 2021, various reports said Toyota was suspending production in Japan. The outbreak of the Delta variant in Thailand and in Malaysia has forced the closure of factories responsible for car parts that would normally be shipped elsewhere for final assembly.

Added on top of the ongoing crisis is the chronic shortage of semiconductors.

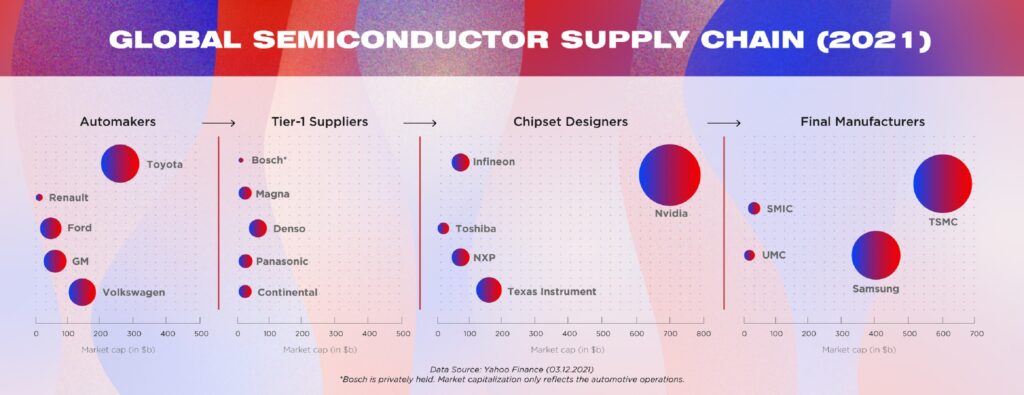

Toyota, the true master of supply chain management, had stockpiled chipsets ahead of time. Unlike GM or VW, the company possesses a formidable online system that had warned its management team of the impending crisis. The system contains a comprehensive database that stores supply chain information for around 6,800 parts. Every day, every week, every month, Toyota communicates with thousands of suppliers at all levels. This is in part why Toyota has achieved the number two position in the IMD’s Future Readiness Indicator.

But despite its preparation and the accurate forecast, the previous inventory of semiconductors eventually ran out. And now Toyota will be the latest company joining the woes of other automakers in missing consumer demands, and thus earnings.

That global shortage of chipsets hasn’t escaped the notice of government. US Vice President Kamala Harris made the trip to Singapore last Tuesday to speak with executives at companies ranging from GlobalFoundries to 3M. She said, “When we look at the disruption to the supply chain, this is an issue that requires all nations… (to) work together to coordinate.”

The shortage of chipsets is no longer just a commercial concern. It’s becoming a national priority, because further price increases in cars and consumer electronics could threaten the U.S. with unabated inflation.

So here’s the obvious question. What’s the lesson learned from all these supply chain disruptions?

Don’t Compartmentalize the World

You may not think narrowly at home. But at work, you are likely be responsible for a functional role. So it’s natural to prioritize giving your attention to things in “your lane.” That’s why the head of R&D looks at technologies, public affairs looks at governments, production looks at factories, and it’s only the procurement person who monitors the global supply chain.

But the outside world doesn’t care how your company organizes itself.

What Toyota facing is the convergence of several deep problems. Each problem is unpredictable, and they compound into a complexity that renders any forecast useless. Think about it: Governments in Thailand and Malaysia have no choice but to shut down local factories. And that’s because of the Delta variant, which is a random act of nature.

Geopolitical tension means that China lacks easy access to American technologies. Then there’s the technological progress that demands ubiquitous connectivity. And so a car has become a supercomputer on wheels, which in turn raises the demand for semiconductors. And China has yet become self-sufficient in semiconductor production. Without access to the latest technologies, China simply can’t ramp up production of chipsets as if it was making sneakers.

Predicting the outcome for each of these problems can be exceedingly difficult. It’s simply impossible to map out the final outcome when these problems interact, with their overall effect multiplying. In this case, prediction is useless. What’s needed is to simplify the system. Smart companies do not predict when and where things will go wrong. They build redundancies so the system becomes more robust. And this is the ultimate lesson for everyone.

But before we get into that, we must dive deeper to the current craze of the global supply chain. Because as the shortage looks dire, we are likely to reach a stage a few years down the road where capacity could far exceed demand, just like with the current surplus of crude oil. The boom-and-bust cycle is notorious not only in oil, but also in minerals and input materials of all sorts. And the more “optimized” and “efficient” a system, the bigger such a swing will be. The semiconductor industry just happens to be one of the most “optimized” sectors the world has created.

The Longer the Supply Chain, the Bigger the Bullwhip Effect

Long before we had our internet economy, researchers at Stanford in the 90s observed that a small change in consumer demand for baby diapers at Walmart could trigger much larger changes in Walmart’s wholesale orders to P&G. And that set off even bigger swings in P&G’s demand for the input materials like wood pulp and polyester fabric. The small shifts in the demand for an end goods always ripple up the supply chain like a cowboy cracking a bullwhip. The hand may move only by inches, but the tip of the whip snaps several feet through the air. Hence, the “bullwhip effect” of the supply chain.

There are numerous reasons for this. Poor demand forecasting, price fluctuations, and a lack of clear communication among suppliers are the usual causes. But the biggest issue is fear.

When people started working at home last year, they bought more electronic gadgets. Makers of phones, laptops, game consoles were ramping up production. They ordered more semiconductors. That had created a sudden surge in demand for suppliers like Qualcomm and NVIDIA, which design and sell the chips found in everything from Nintendo Switches to iPhones. Then in the second half of the year, the economy started to recover, and people were also buying cars. All these suppliers were then putting in their own waves of extra orders with the upstream suppliers—manufacturers like TSMC in Taiwan or Samsung in South Korea.

Here is the big problem: TSMC alone commands about 50% of the market share of all semiconductors in the world. But semiconductor production is not something you can ramp up quickly. Setting up a semiconductor factory requires an upfront investment of as much as $12 billion. And the factory takes three years to become production ready.

Just like in a famine, everyone is now ordering even more since supply becomes scarce. Every company is trying to stockpile chips to last them through the crisis. Even highly experienced tech companies such as Nvidia, Microsoft and Apple are struggling to receive a steady supply. That only triggers further panic buying. The only winners are, predictably, TSMC and Samsung, who have seen their share prices rise by 190% and 61%, respectively, in the past 12 months.

How Smart Companies Will Escape The Boom-Bust Cycle

How companies respond to a crisis is just as telling as how the crisis occurs. Auto-parts maker Bosch, with its chairman, came out to admit the supply chain for auto chipsets is broken. But not much we know how to the industry should be fixed. Tesla, on the other hand, found its own solutions. Elon Musk doesn’t expect much from his industry partners. He is rewriting the car firmware himself, so that he can source new type of chipsets all together.

Here is the big problem: TSMC alone commands about 50% of the market share of all semiconductors in the world. But semiconductor production is not something you can ramp up quickly. Setting up a semiconductor factory requires an upfront investment of as much as $12 billion. And the factory takes three years to become production ready.

More specifically, he works directly with TSMC and Samsung, thereby pushing out the old middlemen of all kinds within Tesla’s supply chain. In other words, Tesla is using its software muscle to take over more functionalities that used to be located in the more purpose-built hardware. That hardware historically been put together by Bosch, Infineon, and many more in a long chain. Tesla is shortening the supply chain on its own.

That’s an approach that obviously requires some deep understanding of software programming. And among carmakers, despite everyone talking about autonomous driving and connectivity, only Tesla has the real capability to make it work.

But what Tesla going for is not just shortening its supply chain in the near term. What it does will result in a new arrangement on how a car is built. When that happens, the company can then solicit more suppliers around the world to meet its chipset requirements in the long run. Tesla’s statement reads, “Our electrical and firmware engineering teams remain hard at work designing, developing and validating 19 new variants of controllers in response to ongoing semiconductor shortages.” Nineteen variants is exactly the creation of redundancy.

Sure, redundancy would be more expensive to maintain. Working with two versions is always easier than working with 19 variants. Maintaining a list of 25 suppliers, for instance, is always more time-consuming than working with just five, with each new supplier requiring additional handholding. But having a deep relationship with only a handful of trusted suppliers can yield a system too vulnerable to withstand external shocks.

This conclusion should not be surprising. If everything is optimized to the extreme and running close to 100% utilization rate, it’ll surely be very cost effective, but also on the verge of implosion. This is why Google and Amazon have redundancies in their computer servers around the world. This is why their customer data are duplicated and stored in multiple locations. It’s a more expensive approach, but this is how tech giants avoid catastrophic outcomes. Executives will never yield to Wall Street analysts’ pressure to eliminate redundancy in order to save those tens of million in expenses.

What’s interesting here is when it comes to semiconductors, traditional carmakers have no clue. They’ve been closing their eyes to activities that lie outside their own companies. As long as there’s a contract in place, they thought, they would be safe. Except of course, there are times when perfect drawn contracts are not even enforceable no matter how loud you scream.

What Growth You Should Pursue

There are two types of growth. There is growth that scales a company in size but turn its increasingly vulnerable. In this case, executives rely on scenario planning and forecasting to talk themselves into believing any uncertainty is managed and controlled. Then there are companies that choose to grow while at the same time building buffers. Their buffers increase in the same proportion as the enterprise scales. Why? Like legendary investor Ray Dalio once said, “Make sure that the probability of the unacceptable (i.e., the risk of ruin) is nil.”