Rebuilding supply chains in the age of tariffs

As Trump-era policies return with sharper edges, companies must rethink supply chains not for speed, but for resilience. ...

by Ralf W. Seifert, Richard Markoff Published June 20, 2023 in Supply chain • 5 min read

Lying at the intersection of economics, trade, geopolitics, and operations, the semiconductor supply chain has taken an outsized role in the public consciousness. Over the last two years, the shortages, their complex origins, and their economic impacts have placed this small, ubiquitous component at the heart of a growing movement towards supply chain resiliency.

By now, most people know that semiconductors are microchips used in mobile devices, computers, digital networks, automobiles, industrial machinery, and domestic appliances. So vital are these components, in fact, that it would be difficult to imagine a successful economy without a secure, steady supply.

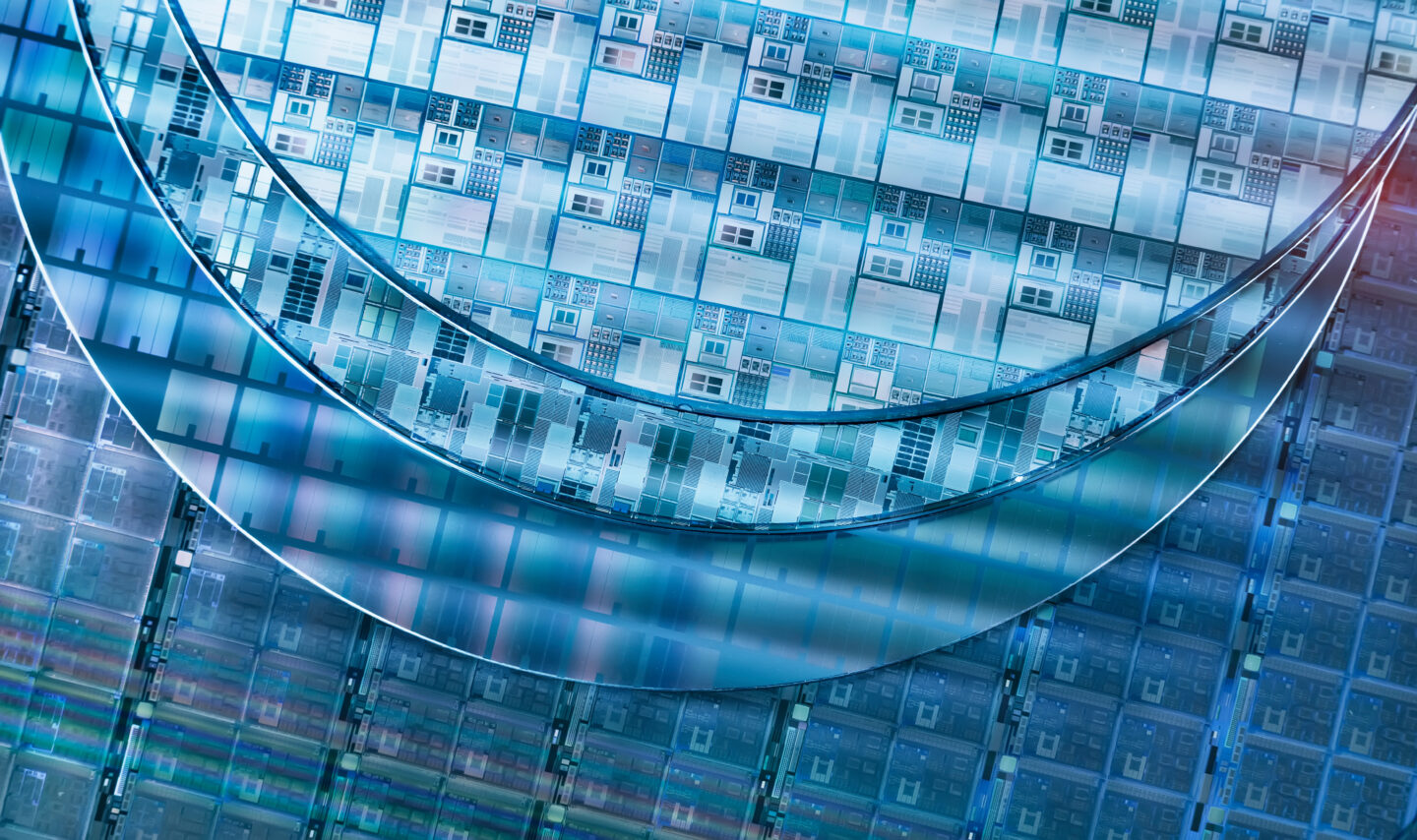

The shortages, caused by a powerful blend of geopolitics and demand patterns disrupted by the pandemic, have collided with the widespread realization that semiconductor manufacturing is deeply concentrated in Taiwan. This confluence of events has made semiconductors the most prominent example of a growing movement of bolstering both supply chain resilience and economic independence through onshoring.

A closer look at the changes underway in the semiconductor supply chain show that some unintended consequences might be in the offing, demonstrating some fundamental supply chain principles.

The most prominent example of public policymaking in the semiconductor sphere is the CHIPS Act, passed by congress in the US in the summer of 2022. This act provides $52bn in funding and incentives for the construction of domestic semiconductor manufacturing. Intel, TSMC, and Samsung have already announced plans to build four factories in the US, with more under consideration. If these sites are completed, US share of global semiconductor manufacturing would rise significantly from its 12% of global supply vs. 37% of global demand.

But the US is not the only country concerned about its ability to secure a reliable supply of semiconductors.

China has attempted to provide $145bn to increase its domestic semiconductor manufacturing capability, with mixed results. This initiative is stymied, in part, by the Biden administration’s efforts to limit production technology exports to China.

“When a resource is divided up, more of it is required to meet demand.”

Similarly, the EU is determined not to be caught flatfooted in this race to semiconductor autonomy. The EU Chips Act, currently in negotiation, aims to increase its share of semiconductor manufacturing from about 10% to 20% through roughly €43bn in funding for factory construction and research, among other initiatives.

It doesn’t stop there. In 2022, Canada announced its intention to invest $240m CAD to scale up its semiconductor ecosystem, though that sum seems paltry compared to their counterparts. Meanwhile, Japan is considering their own program to return the country to being a major player in semiconductor supply, and in a similar vein, Korea is aiming by 2030 to secure 50% of the materials, components, and equipment for its own semiconductor manufacturing base.

On the face of it, these efforts to generate incremental semiconductor manufacturing capacity are not necessarily problematic, with the industry projected to grow by 12.2% each year. However, the objective of these programs is not simply to generate new manufacturing capacity, but to generate domestic manufacturing independence. Even if one sets aside whether this is realistic without considering materials and equipment sourcing, it carries significant implications for supply chains in the future.

Very few supply chain principles always hold true regardless of context or industry, making it a difficult subject to teach – and to learn. One of them is that when a resource is divided up, more of it is required to meet demand. To illustrate this, imagine a warehouse. If any product can be stored in any part of the warehouse, less space is needed overall than if it is divided into dedicated sections for different products. In this scenario, each section would need surplus space because it cannot look to other sections when it happens to be full.

The same is true for manufacturing capacity. If each major market strives to have sufficient capacity to meet its internal demand, then the result is that overall global capacity is much higher than if the capacity were not divided. This effect is compounded by the decreased efficiency of having less volume on each production equipment, which diminishes machine productivity and operator expertise. This principle – the concentration of volume allowed for capital utilization and efficiency – is what drove large companies years ago to consolidate production.

As each market seeks to secure and exploit domestic production capacity, each will have smaller technology clusters, less asset utilization, and higher labor costs. The result of these initiatives may well be that the future semiconductor supply chain will involve lighter machine loads and higher unit prices, despite the ambitious growth projections.

In a way, what we may be seeing is a sort of bullwhip effect, but not one where the result is higher production – at least not yet. This particular bullwhip is one of capacity generation unmoored from true demand, and it is something worth keeping a close eye on.

Professor of Operations Management at IMD

Ralf W. Seifert is Professor of Operations Management at IMD and co-author of The Digital Supply Chain Challenge: Breaking Through. He directs IMD’s Strategic Supply Chain Leadership (SSCL) program, which addresses both traditional supply chain strategy and implementation issues as well as digitalization trends and the impact of new technologies.

Supply chain researcher, consultant, coach and lecturer

Richard Markoff is a supply chain researcher, consultant, coach, and lecturer. He has worked in supply chain for L’Oréal for 22 years, in Canada, the US and France, spanning the entire value chain from manufacturing to customer collaboration. He is also Co-founder and Operating Partner of the venture capital firm Innovobot.

June 20, 2025 • by Carlos Cordon in Supply chain

As Trump-era policies return with sharper edges, companies must rethink supply chains not for speed, but for resilience. ...

May 13, 2025 • by Simon J. Evenett in Supply chain

As tariff tensions simmer and uncertainty clouds the future of global trade, freight industry leaders reflect on how businesses can brace for potential shortages, adapt supply chains, and stay resilient in a...

April 29, 2025 • by Ralf W. Seifert, Katrin Siebenbürger Hacki in Supply chain

Magdi Batato, a former Nestlé executive, has spent over three decades shaping global supply chains and operations in one of the world’s largest food and beverage companies. In his new role at...

April 28, 2025 in Supply chain

As global trade tensions and US tariffs disrupt conventional supply chains, corporate leaders must reconsider resilience through strategic diversification, regionalization, and risk management in order to remain competitive in an increasingly protectionist...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience