IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Published in December 2021

Not All ESG Efforts Are the Same; Companies Need to Specialize

Published in December 2021

Corporate social responsibility is big business. Fortune 500 companies have collectively spent $20 billion on such efforts but it’s a tiny drop in the ocean when you consider it’s only about

However, looking at expenditure is misleading. You can’t judge a company’s innovativeness by counting its R&D spend. Nokia, for one, outspent Apple nine times on R&D, yet still lost out in the smartphone battle.

This is why it’s hard to gauge a company’s positive impact. You certainly can’t only look at the amount spent: some may lavish on sustainability initiatives; others may set up corporate foundations; still others may sponsor employee volunteer programs or make donations to charity.

But this spending increasingly has the feel of buying forgiveness. Too often, we hear about the terrible things that businesses commit on a regular basis: oil spills, deforestation, selling our data to the highest bidders. That’s just another way of saying that charity alone can’t turn a company into a force for good.

Sideshows don’t matter; the public judges a company by what it really does. And if a company doesn’t have a strategy that feels authentic, it risks being seen as greenwashing.

What companies need to do is develop a set of goals that are directly related to their underlying business strategy. Gaining traction in environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) is not easy, but it’s straightforward. A company builds the ESG agenda into its business model, because if it’s not part of the flywheel of its core operation, it will not go far.

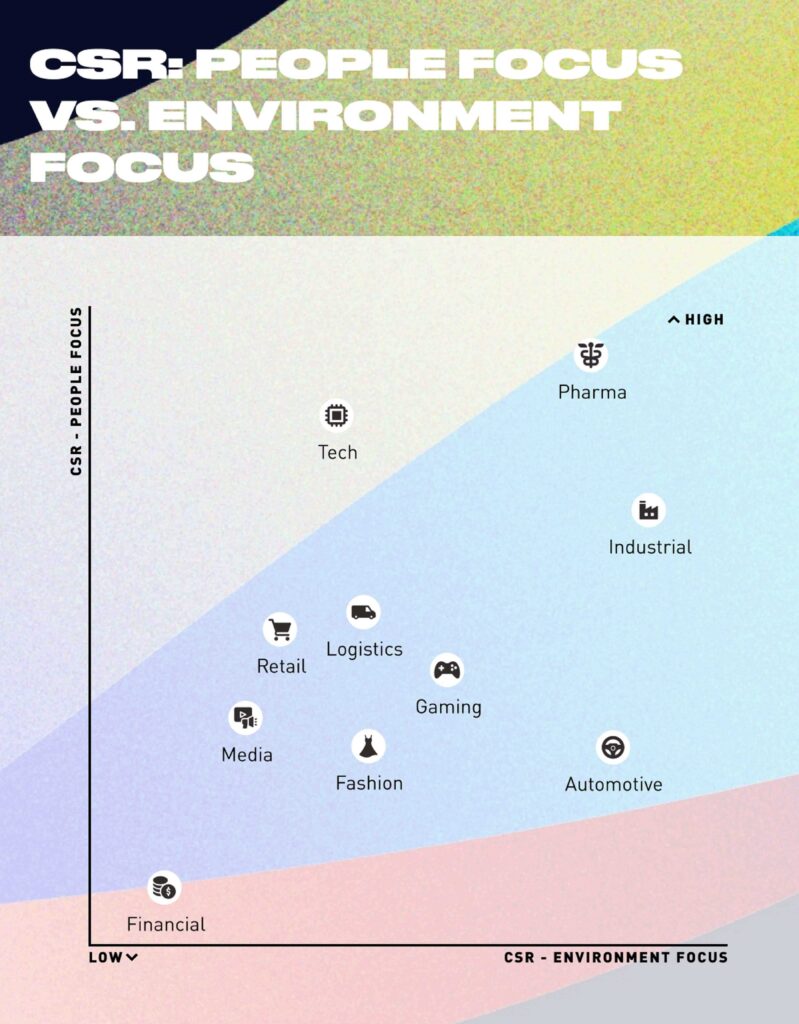

The ESG arena is vast, with any visual analytics risking oversimplification, but let’s look at the patterns. In the graph below, the X-axis depicts efforts that go toward the environment. The Y-axis depicts efforts that focus on society and the community. In short, one is for the planet, the other is for people.

We reached this result by feeding an algorithm with 10 years’ worth of business coverage. We did this because there are no uniform reporting standards and ESG reports are not easily comparable. A study published by the Harvard Business Review in May pointed to exactly this problem. Ninety percent of the largest companies produce ESG reports, yet only a minority of them are subject to third-party validation. The contrast with financial reporting in annual reports is stark. Those numbers are subject to the scrutiny of independent auditors, but ESG reporting is not so the data remains inconsistent.

Our computer-aided analysis seeks to overcome such difficulties. An algorithm scores ESG-related activities as reported by more than 60 business publications over the last 10 years, reflecting what companies have done. We then tease out these companies’ behaviors. This method is commonly used by academic researchers and you can read about our detailed methodology here.

This is what we have learned. As shown in the above graph, industries tend to specialize, and manufacturing industries like automotive and industrial goods are material- and energy-intensive. Naturally, they concentrate on environmental impact.

This is hardly a selfless motive. Sustainability initiatives, when applied to a factory’s operations, can reduce resource use and waste, in turn reducing costs. When an initiative aims to reduce carbon emissions, the business can lower its fuel cost. Then it can also trade carbon credits in the open market, thereby earning additional revenue. Tesla, for example, has been selling environmental credits for a long time. It was a main source of income before it was producing electric vehicles profitably. Tesla wouldn’t be even around had it not been able to sell carbon credits.

Put another way, companies must develop coherent ESG strategies. Without such, deciding on capital allocation is all but impossible. Only by focusing can a company have meaningful results.

How the global supply chain is not planet-friendly

Our analysis also highlights some worrisome trends. The logistics industry has been lagging far behind. Freight transport is a key battleground for climate change, accounting for around 30% of all transport-related CO2 emissions.

This lack of progress reflects how fragmented the logistics industry is. Players such as freight forwarders and trucking companies are often local and small, and don’t have the resources to invest in new equipment. They tend to run on existing, fully depreciated assets as long as they can. The a freight forwarder’s situation is a world apart from that of an automaker like VW. A trucking company simply can’t marshal resources in the same way as an industrial giant such as Honeywell. In heavy industry, big companies have the size and scope to invest, and one major play can have a disproportional impact on the environment.

By extension, investments in employees also yield direct benefits. A company can improve its working conditions, provide better health care, or choose to invest in employee training. Doing so can bring higher productivity and the company may retain key talent. At the very least, such actions can improve a company’s reputation. This is why tech giants are pouring resources into this area. The need to attract talent is far too strong, And perhaps more importantly, public scrutiny over their business conduct has increased by so much That they are scrambling to save their reputations.

There’s always somebody who never learns

There’s one industry that never learns, and that’s finance. Whatever banking executives say they’ve already done, the industry hasn’t made much progress. Bankers are often portrayed as disconnected from the larger reality. The stereotype of an arrogant, out-of-touch banker does bear some truth; and the public can’t shake off the image of how smug and entitled they are. The constant reporting about bankers’ conspicuous consumption doesn’t help, while their indifference about the impact their decisions might have on everyone else continues. From a cross-industry analysis, the stereotype is not entirely incorrect.