IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Published in December 2021

Two Charts that Explain How Apple Loses to Spotify in Podcasts

Published in December 2021

How does a company, having invented a whole category of product, lose it to a competitor? I am not speaking of a slow-reacting organization. I am speaking of Apple and its podcasts.

Podcasting started off with iPods. For years, it’s been one of Apple’s mainstays. Podcasts took off during the pandemic lockdown, and its market is projected to bring in more than $1 billion in revenue this year from advertising in the U.S. for the first time.

Also in this year, the number of Spotify’s podcast listeners is set to overtake Apple’s.

Apple didn’t stopped or stagnated. Its service still grew, but it’s losing market share. From 34% in 2018, it has dropped to 24% in 2021. Meanwhile, Spotify now carries 2.2 million podcasts, up from 450,000 back in 2019. To achieve this, Spotify is taking a page from Netflix’s playbook by acquiring exclusive content and forging partnerships for wider distribution. It moves faster than Apple in exploring what is possible for the audio service.

The question is: how could Apple let this happen under its watch? What does Spotify have that Apple doesn’t?

To answer these questions, we took the big data approach at the Center for Future Readiness at IMD. We downloaded 10 years’ worth of business publications, including the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, company’s press releases, and others. We fed all of them into an algorithm. The algorithm then aggregated how companies talked about themselves and how the business community came to understand them.

Such textual analysis is not the perfect measurement of company’s behaviors, but it should give us a reliable gauge on how things have evolved. You can read up our methods here.

Let’s look at the industry context first. The tech industry is a tough industry. Apple and Spotify are competing in a sector where changes happen frequently and drastically. A company that enjoys a blockbuster quarter can miss its earning expectation badly a few months later. Success depends on the ongoing ability to deploy innovative and popular apps.

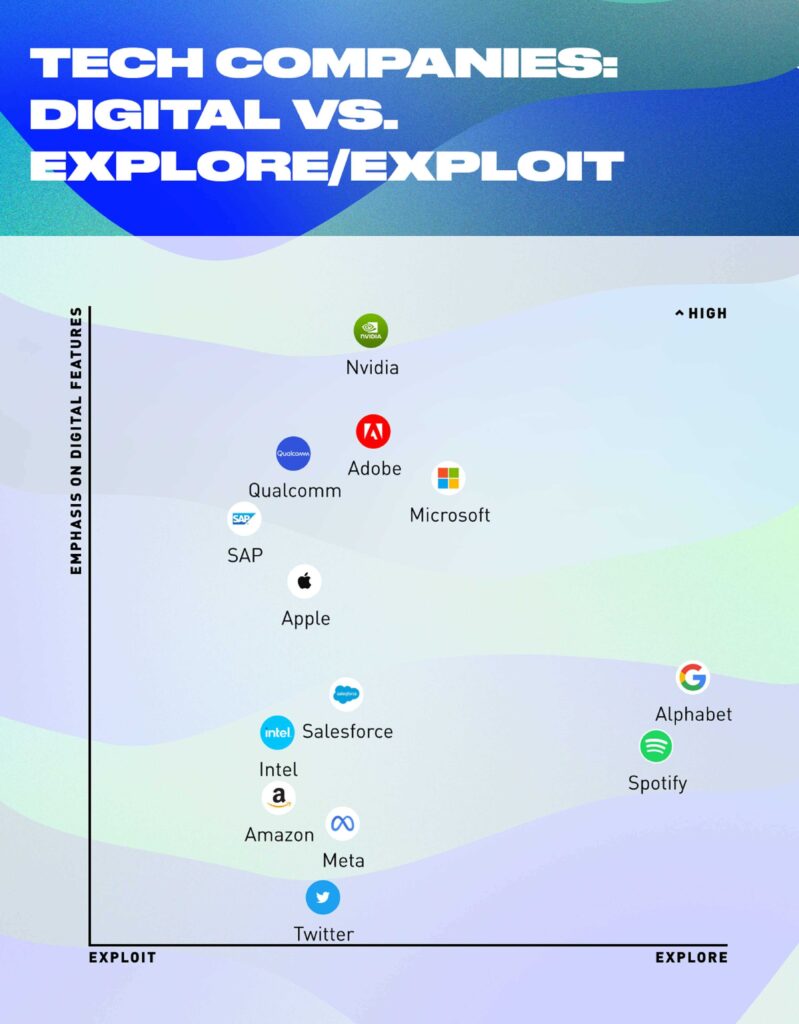

Even so, the chart below demonstrates a subtle difference among tech companies. There are tech companies who trumpet their digital sophistication. Technology providers like Nvidia or Qualcomm or SAP reflect this trend. For these business-to-business (B2B) companies, they lavish on functional specifications, processing power, and network bandwidth. Technology features is the selling point.

The same is not true for consumer brands. Any consumer brand that succeeds in the technology sector has to make its technology disappear. Mainstream users only care about a seamless experience; that’s all. The technology involved must operate silently in the background. And that shows according to our Y-axis.

On the X-axis, we capture the construct of “exploit” versus “explore.” A company must be able to exploit near-term opportunity in order to pay today’s bill. You have to be good at maximizing your current advantage. But if you only focus on the near term, then the future will be grim. Some effort must be spent in exploring new areas. Exploration like research and development, invention, and creative thinking are critical to a company’s long-term survival. Explore and exploit are not mutually exclusive choices. You must have both.

And, yet, success still depends on who you are and the nature of your business. You have to strike a balance unique to you. If your operation carries a huge factory, like that of Intel who makes semiconductors, you need to have a strong dose of discipline. Letting your factory run wild is a sure way to bankrupt the company. Even at Amazon, its network of fulfillment centers demands discipline and rigid standards.

In contrast, software-driven companies like Google and Spotify can lean further towards exploration. Why? If you write a code wrong, you can roll it back the next hour. If you launch something in the market that doesn’t work, all you do is an update over the air. But the digital magic stops where the physical atom begins. That’s why capital-intensive companies tend to be cautious and more conservative. They exploit more often than they explore. It’s all out of necessity, as indicated by the X-axis.

So how did Spotify make its killing?

Spotify needs to endear itself to podcasters. The more podcast creators there are on the platform, the more attractive Spotify becomes for listeners. With that in mind, it grants access to data to creators early on. It lets them see data like listeners’ music taste, age, gender, location, and how long they listen to a particular episode.

Then Spotify acquired the podcast software company Anchor for about $100 million in 2020. It’s not only big networks like NPR, The New York Times, and Wondery that Spotify is courting. It wants any micro-celebrity, no matter how niche their audience is, to start recording episodes by, start turning on a button over their laptop. To encourage people further still, Spotify’s Anchor supports monetization and automatically inserts ads into participating shows. It lets podcasters offer subscription podcasts without taking any revenue cut.

Still, all this focus on small-time podcasters didn’t stop Spotify from luring big stars. It signed exclusive deals with figures like Joe Rogan, Kim Kardashian West, and Michelle Obama. No matter what your inclination is, you’ll find someone you adore exclusively featured on Spotify.

That’s it. It’s an arms race across multiple frontiers: user experience, creator experience, and original content. And Spotify, across all fronts, is moving faster than Apple, as the data shows.

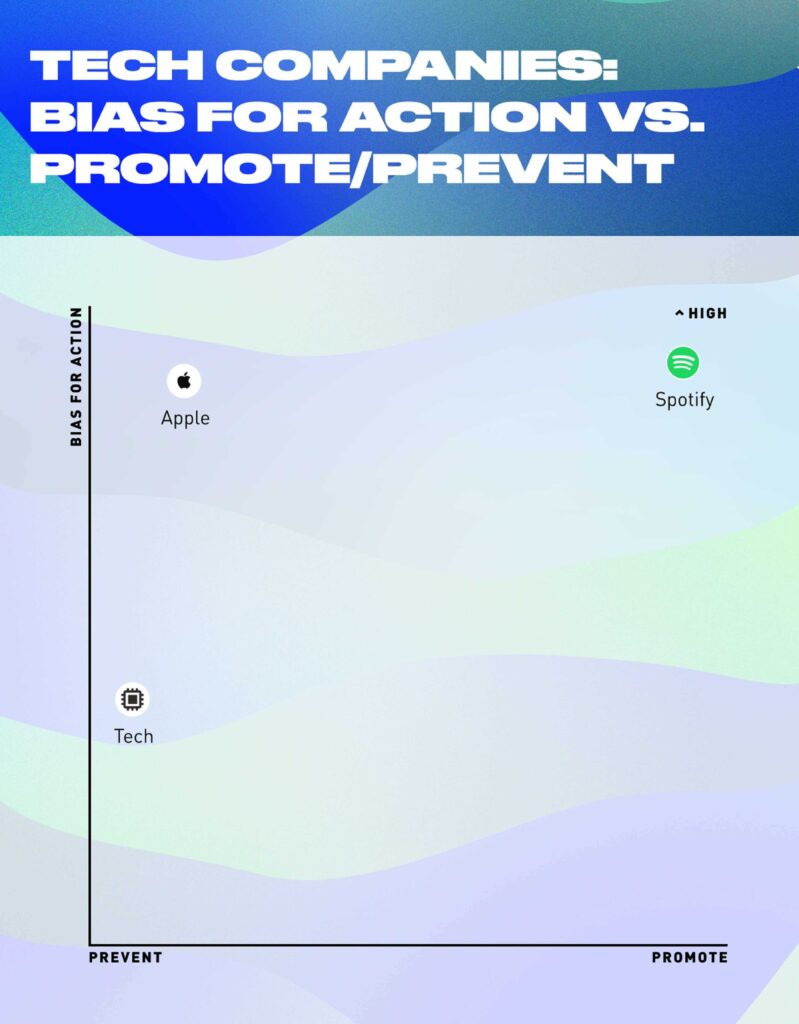

In the chart above, we see the bias for a company to try new things along the y axis. Essentially, this graph asks, “Are they more inclined to act or they are more inclined to plan?” On here, both Spotify and Apple are proactive. Then, along the x axis, you see the differences in their risk outlook. Here we see whether the organization acts preventively in an effort to avoid catastrophic outcomes as its primary concern or, conversely, whether a company sees opportunities everywhere and determines to seize them before they disappear.

Despite, their shrinking influence in podcasting, there remain legitimate reasons why Apple behaved the way they did. It’s a company so big that podcasting is a market too small for it to pay much heed to. It’s also a company whose brand is synonymous to perfection. Mistakes must be avoided. It also has a network of complex supply chains that it must run efficiently without the leeway for wasteful spending. It’s a highly profitable company overall, and these are the foundations of Apple’s successes.

And precisely because these are what Spotify is not, Spotify is winning when it comes to podcasting. It’s a smaller player, it has less risk aversion, and it is playing to win. Apple, meanwhile, is playing not to lose.