William McDonough and Michael Braungart, pioneers in green design, are credited with the following analogy, “If a car is heading south, slowing down does not cause it to head north. Sooner or later you need to turn the car around 180 degrees.”1 In order to tackle the enormous social, economic and environmental issues on the horizon, we can no longer afford to continue with “business as usual” – we are already using 50% more resources than the planet can provide and will need the resources of three planets to sustain our growing population by 2050.2 In reality, even the organizations that are at the forefront of the corporate sustainability movement have only managed to put on the brakes and slow down the rate of social and environmental damage. What the world needs now are more enlightened organizations that are willing to turn their businesses around and embark on truly restorative sustainability journeys.

In this article, we examine the corporate sustainability journey in the context of resource scarcity. We describe the typical journey a company takes from the first reactive and defensive stages to more proactive stages, embedding sustainability into its DNA and fully reaping the cost savings and revenue benefits associated with this more holistic approach. However, we argue that while this improvement is important, it does not go far enough in addressing a business’s social and environmental impacts. The unexplored territory in the sustainability journey lies beyond this traditional trajectory – where some companies are striving for a net zero impact on the environment or even a restorative effect by leaving the world a better place than when they began operations. These companies are demonstrating how it is possible to completely rethink “business as usual” and begin to address the world’s largest problems from an entirely new direction.

What is sustainability anyway?

What do we mean by sustainability? Sustainability is a difficult concept to define and the confusion surrounding the term has been shown to be one of the key barriers to adopting a fully integrated sustainability mindset.3 In fact, there are so many similar terms out there – corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate citizenship, triple bottom line (TBL), stakeholder management, industrial ecology, the circular economy, natural capitalism, cradle-to- cradle, and so on – that it is no wonder confusion persists. Add to that the many other initiatives that fall under the umbrella of “beyond the economic and legal mandate of the firm” (e.g., employee relations, diversity, safety and ethics) and the picture becomes even more muddled.

Both practitioners and academics seem to have converged on sustainability as an overarching theme that encompasses many of these terms. Sustainability in an organizational context requires firms to adhere to the principles of sustainable development, which has been defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”4 Or, more simply, sustainability has come to mean “enough, for all, forever.” This means that for industrial development as a whole, and business in particular, to be sustainable, we must address important social and environmental issues that may have previously been considered beyond the traditional responsibilities of the firm.

Planetary boundaries and resource scarcity

The deep changes that are needed to solve some of the world’s largest problems – including social equity (e.g., poverty, health and wellness, and human rights) and environmental accountability (e.g., climate change, land use and biodiversity) – are going to take a totally different kind of approach to sustainability that acknowledges a new future of global resource scarcity.* Evidence suggests we have already transgressed the planetary boundaries in biodiversity, climate change and nitrogen inputs.5 It is expected that we will hit the critical tipping point of a two degree increase in global temperature in the next 12 years.6 After this we are likely to start to see issues with basic needs such as food and water. Over 1 billion people already live in countries and regions where there is insufficient water to meet food and other material needs. By 2025, this number will grow to 1.8 billion, with two-thirds of the world’s population living in water-stressed regions.7

What makes these statistics so scary is that their effects will now be felt within our lifetime and if not, certainly the lifetimes of our children. These scenarios, even if they are off by a couple of years, or even a decade, mean that we are entering a world in which companies can no longer operate on the paradigm of abundance, but rather must shift their thinking to one of scarcity. Research shows that many firms are not prepared for a resource scarce environment and are “sleepwalking into a resource crunch.”8 Given that environmental areas such as carbon emissions, water, waste, oil and gas, grid energy and rare earth metals are predicted to become of critical importance, firm- level response to the resource scarcity issue is critical. In this context, what role can companies play? First of all, it is important not to be paralyzed by these statistics and decide that the problems are too big, or too difficult to tackle. It is also important that businesses move beyond the traditional “shifting the burden” archetype and stop claiming that these issues are not theirs to solve.

Stages of the sustainability journey: Traditional and new pathways

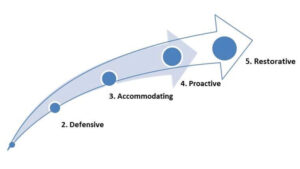

Many companies have started to address social and environmental issues through corporate sustainability initiatives. The typical journey to sustainability within organizations is difficult to generalize as each one is unique and embedded in a particular industry and context. There are also examples of companies that are “born sustainable,” as is the case with social or environmental entrepreneurs. But overall, one can say that historically, most companies go through five stages in their sustainability journey (see Figure 1):

- Reactive. Businesses are first confronted with a social or environmental issue they have not previously considered and are forced to react to some form of stakeholder pressure that they are ill-prepared for.

- Defensive. Companies may go on the attack to try to prevent changes in their operating environment. The defensive stage can include litigation or excessive lobbying against new regulations that they perceive will threaten the status quo.

- Accommodating. Organizations concede that the sustainability issue is here to stay so they might as well adapt to it. Accommodating strategies can range from compliance to what might be called compliance plus, but it is still essentially doing the bare minimum in terms of what might be expected either by law or by the ethical norms of the environments in which they operate. Here organizations are trying to avoid fines, prosecution or bad PR. If they’ve moved to beyond compliance, they may be starting to look at their internal practices to see where they may be most at risk and developing strategies to address these issues.

- Proactive. Companies move from seeing sustainability as a challenge to seeing it as an opportunity. They start to see it as something that could actually enhance company value either by reducing costs or increasing revenues. For example, companies begin to redesign selected existing products and processes in new ways (see The benefits of being proactive).

The benefits of being proactive

Being proactive provides many opportunities to reduce costs through better managed resources (e.g., reduced energy usage, reduced waste, reduced materials). For example, Maersk Line, the world’s largest shipping company, saved $1.6 billion in fuel costs by cutting its CO2 emissions per box by 25%.9 Another example is Walmart’s claim that the changes it has made in converting to renewable energy and reducing the energy intensity of its stores by 20% will result in $1billion in annual savings by 2020.10 Being proactive can also involve introducing new products or services that are born of a new way of seeing sustainability. The opportunity to increase revenue from new products or services has been shown to add to the top line. For example, more than half of GM’s facilities are now landfill-free – all waste is reused, recycled or converted to energy. By selling its waste, GM is now generating more than $1.5 billion per year in revenue – money that it used to throw away!11 On a larger scale, GE’s Ecoimagination products and services have delivered over $100 billion in revenue since the project was launched in 2005.12 Obviously, not all savings or earnings will be on this scale, but they are all important to the bottom line. Simple things like removing light bulbs from soft drink machines in employee break rooms have saved Walmart $1 million per year.

Most research into the stages of a company’s sustainability journey ends here.13 However, we argue that to be truly sustainable, one last stage remains:

5) Restorative. Senior leadership commits to fully embrace sustainability as part of the organization’s core values, where the business is seen fully as part of a larger system and the entire business model is redesigned with sustainability in mind. This means that the organization makes commitments: to take nothing from the earth that cannot be replaced; to release nothing into the atmosphere that cannot be recovered; and not to contribute in any way to conditions that undermine people’s capacity to meet their basic human needs now or in the future. These enlightened firms strive for at least a net impact of zero on the environment and societies in which they operate, and envision a business model where their operations can eventually have a generative and restorative impact – leaving the world better off than before it existed.

Example: Natura Cosméticos

One example of a company on the journey to the restorative stage is Brazilian cosmetics maker Natura Cosméticos. The company manufactures skin treatments, bath products and fragrances by sourcing most of its ingredients domestically and supporting small suppliers in rain forest communities using a fair trade model. The company’s leadership has committed to embrace a holistic strategic vision of sustainability:

We will integrate triple bottom line (economic, social and environmental) management into all company processes, with innovative, leading-edge business practices that inspire others, making Natura a role model in business conduct. This new vision expresses Natura’s wish to go beyond simply reducing or offsetting the effects of its activities on the environment. The intention is to ensure the company generates a positive impact on society and on the planet.14

As a founding member of the Union for Ethical BioTrade, Natura ensures that it sources its ingredients sustainably without harming biodiversity, while assuring the equitable sharing of benefits all along the supply chain. Through its Programa Amazonia initiative, the company invested in the Ecoparque — a 1.7-million-square- meter industrial park in the Amazon region aimed at attracting companies interested in developing sustainable businesses and supporting local communities. The facility aims to develop a closed-loop system by selling the bi-products of producing cosmetics from Amazonian fruits, oils and berries to other co-located companies in complementary industries. Raw materials will come from traditional communities in the Amazon and 90% of employees from local communities. Through this initiative and others, the company is in the process of creating restorative impact by involving suppliers and other stakeholders establishing sustainable business ecosystems.

Natura has been identified – along with Ricoh, Puma, Nike, Nestle and Unilever – as a global company ready for a “green and inclusive economy” that has set measurable and ambitious mid- to long-term targets to make it more sustainable.15 While these companies cannot be said to have “completed” the journey to sustainability in that they have not yet fully reached the restorative stage, their actions have been exemplary in many regards and they can be lauded for much of what they have accomplished.

So now what? Where do we stand?

So what does this all mean for you? A good place to start is an honest assessment of what stage your organization is really at on the sustainability journey (see text box below). At IMD, we asked participants in several programs about sustainability in their organizations and 54% claimed that it is already fully embedded in the strategy of their operations.16 And yet, when pushed further, most admitted that their organizations are taking a very narrow view of sustainability and are likely only in the accommodating or early proactive stages. Few organizations are actually embedding sustainability throughout every process and fewer still are rethinking their fundamental business models around a systemsview of sustainability that is restorative.

Where is your company on the sustainability journey? Ask yourself:

- Can our approach to sustainability be described as: reactive, defensive, accommodating, proactive or truly restorative?

- Have we mapped out our full system, conducted a life-cycle analysis of all our products, services and operations and understood the major social and environmental issues that we may need to address today and in the future?

- Have we laid out detailed plans for how we will deal with the impeding resource crunch and how material shortages will affect our business?

- If we could redesign our processes, products and operations from scratch today – from a resource scarcity perspective rather than the abundance paradigm – what would we do differently?

- What are organizations that are already embracing a restorative business model doing differently, and what can we learn from them?

Reaching for the Restorative: The long journey ahead

While the first stages of the typical corporate sustainability journey are a great start, they do not guarantee the real change that is needed to solve the big issues around resource scarcity. After assessing where your organization is on the sustainability journey, you can gain a greater understanding of the total impact of your business by integrating improved measurement systems. This will allow you to make strategic business decisions based on a broader set of criteria than just financial measures. This could ultimately lead to business transformation and new approaches for value creation and capture. To reach the final level of the sustainability journey – where entire business models are conceived with restorative processes at their core – requires a more holistic approach. Business can no longer operate in a linear take-make-waste business model but must shift their thinking to a circular, borrow-use- return, full systems perspective. Only then will we be able to change direction on the long journey ahead and begin to turn around in the direction of sustainable economic, social and environmental prosperity.

While the first stages of the typical corporate sustainability journey are a great start, they do not guarantee the real change that is needed to solve the big issues around resource scarcity. After assessing where your organization is on the sustainability journey, you can gain a greater understanding of the total impact of your business by integrating improved measurement systems. This will allow you to make strategic business decisions based on a broader set of criteria than just financial measures. This could ultimately lead to business transformation and new approaches for value creation and capture. To reach the final level of the sustainability journey – where entire business models are conceived with restorative processes at their core – requires a more holistic approach. Business can no longer operate in a linear take-make-waste business model but must shift their thinking to a circular, borrow-use- return, full systems perspective. Only then will we be able to change direction on the long journey ahead and begin to turn around in the direction of sustainable economic, social and environmental prosperity.

While the first stages of the typical corporate sustainability journey are a great start, they do not guarantee the real change that is needed to solve the big issues around resource scarcity. After assessing where your organization is on the sustainability journey, you can gain a greater understanding of the total impact of your business by integrating improved measurement systems. This will allow you to make strategic business decisions based on a broader set of criteria than just financial measures. This could ultimately lead to business transformation and new approaches for value creation and capture. To reach the final level of the sustainability journey – where entire business models are conceived with restorative processes at their core – requires a more holistic approach. Business can no longer operate in a linear take-make-waste business model but must shift their thinking to a circular, borrow-use- return, full systems perspective. Only then will we be able to change direction on the long journey ahead and begin to turn around in the direction of sustainable economic, social and environmental prosperity.

1 McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press, 2010.

2 WWF. Living planet report 2012: Biodiversity, biocapacity and better choices.

3 UN Global Compact & Accenture. The UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study on Sustainability 2013.

4 Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

5 Rockström , J. et al. “A safe operating space for humanity.” Nature, 461(7263), 2009: 472–475.

6 IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.

7 Alexandratos, N., & Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision. ESA Working paper No. 12-03. Rome, FAO.

8 Carbon Trust. Opportunities in a resource constrained world: How business is rising to the challenge. CTC 828, 2014.

9 Sustainable Shipping Initiative. Membership case study: Maersk Line, 2013.

10 Walmart . 2013 Global Responsibility Report.

11 GM. 2010 Annual Report.

12 GE. 2011 Annual Report.

13 For example, Carroll (1979); Henriques & Sadorsky (1999); Buysse & Verbeke (2003).

14 Natura. 2013 Sustainability Report.

15 Deloitte. 2012 Zero Impact Growth Monitor.

16 Mazutis, D., and C. Zintel, forthcoming.