Over 50 executives attended a recent IMD Discovery Event on approaches to strategy. Participants gained insights into how long-lasting companies thrive and renew themselves, often by balancing exploitation and exploration strategies. The event also touched on new business models in an era of technological disruption.

A common definition describes strategy as a tool or set of processes aimed at creating sustainable competitive advantage. The traditional approach to strategy involves analysis, planning and execution, but this is no longer sufficient. Driven by globalization, technology and the social feedback loops on social media, the business environment has changed drastically over the last 20 years. This has led to a massive proliferation of strategy frameworks – over 114 by 2012.1 The business life cycle is now twice as fast, the profitability of industry leaders is reduced by half, and the longevity of winners is much shorter. With large organizations operating in multiple markets and having multiple lines of business, each working in a specific environment and facing different conditions that change over time, strategy boils down to choosing the right approach to winning in the right part of the business at the right time.

The strategy palette

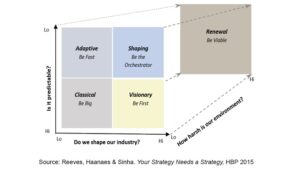

A useful way to present the diverse business environments and the optimal strategic approaches is through the strategy palette.2 It uses three dimensions: predictability (can we predict and plan it?), malleability (can we shape it?) and harshness (can we survive it?). The resulting five types of business environments differentiate the strategy approach best suited for each (Figure 1).

Classical environment

This is host to highly predictable industries with strong brands, high regulation and limited technology change, where winning means being big and efficient. A classical strategy – analyze, plan and execute – is the optimal choice for wining in this predictable environment. Typical examples of companies in this domain include Coca-Cola and Mars.

Adaptive environment

This is characterized by unpredictability and technological disruption. Due to high uncertainty, classical planning becomes inefficient and companies can win only by being flexible and experimentation-oriented. A good example is Zara, which is very adaptive, experiments a lot and produces in small batches.

Visionary environment

Companies and entrepreneurs that operate in predictable industries yet focus on innovations, deploying a strategy that emphasizes visioning and implementation are typical of this setting. Leaders of such companies are visionaries who are not locked into current solutions, traditional ways of thinking. They “see patterns where others see noise.” IKEA is a visionary company that disrupted the industry and does everything to stay ahead.

Shaping environment

Here, despite unpredictability, innovators create an ecosystem of many companies that collectively reshape the industry. “We can’t predict the future, but we can create the game” is the mentality that prevails in such companies, and their strategy is all about influencing, orchestrating and coevolving. Alibaba, Amazon and Apple, with their ecosystems of companies, are excellent examples of players in this space.

Renewal environment

This is characterized by harsh conditions, when a company needs transformation. The strategy should aim not to create competitive advantage but to ensure the company’s survival, by restructuring to free up and redistribute resources. Only when the survival goal has been achieved should the company attempt to deploy another strategy. American Express and Carlsberg Group are good examples of companies that underwent major transformation – and then renewal – when weakening performance initially threatened their very existence.

Evidence from over 200 transformations shows that the majority of companies start transforming only in times of turbulence and underperformance. The first step is operational turnaround (cost cutting, reallocation of internal resources, etc), which lasts about six months until the company recovers and reaches industry-average performance. Yet most companies undergoing transformation cannot sustain the result in the long run, as they tend to stop after the first phase without picking a new strategic approach for innovation and growth.

Successful business renewal

Ongoing IMD research shows that out of the top 50 Fortune 500 companies in the 1970s, only 16 made it to the 2016 list, successfully renewing themselves. All of these companies:

- Balance exploration and exploitation well (see below), though differently.

- Remain market-focused and driven from the outside in, rather than becoming more introverted.

- Are not first movers, but are always early movers. If needed, they make large acquisitions.

- Embrace disruptions without falling into the success trap. Many have in fact disrupted themselves.

- Adopt a portfolio perspective to “owning” their market space. They constantly scan for new ideas, megatrends and key needs, and are not afraid to exit profitable businesses and markets if they will not serve long-term interests.

- Have a culture of building capabilities as they transform.

- Make efforts in the digital and – perhaps surprisingly – sustainability areas.

José Lopez stressed two additional factors contributing to a company’s long-term success: having a profound vision and purpose beyond mere numbers; and the ability to say no to things, in order to find the right opportunity. A crucial step in bringing the vision to reality is operationalizing, described by Lopez as “intending the unintended.” Without it, short-term goals and a narrow focus on numbers tend to overtake mid- and long-term goals. Nespresso, for example, took an intended decision (for technical and strategic reasons) not to sell its capsules in retail outlets, which led to the “unintended” consequence of its product becoming the reference in coffee.

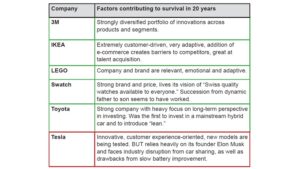

When participants were asked to name successful companies, along with factors that would contribute to their survival over the next 20 years, an interesting list emerged (Table 1). It also triggered a discussion on how success is defined when Tesla was mentioned independently by two groups. Tesla has yet to make a profit, but the value of its future growth is huge.

Table 1: Successful companies: Still here in 20 years?

New business models

Professor Yu spoke about the dramatic changes in business models over the last 20 years, driven by accelerated developments in technology and increased social expectations. The consequences of technological disruption are: reduced transaction costs, increased connectivity, accessibility, scalability and removed entry barriers. Regulators are lagging behind these developments and always have to play catch-up, as in the cases of Uber, AirBnB and blockchain technology.

At the same time, social expectations are higher than ever. Consumer power has increased through user ratings and peer feedback, which are now used to build trust that before was mainly ensured by government regulations. People have grown accustomed to ease of use, efficiency and instant gratification; they have less patience.

With the lowering of entry barriers, new entrants that rely heavily on technological advancements are threatening many existing businesses. For instance, traditional shipping companies are being challenged by small technologically savvy entrants trying out the Uber model for the “last mile” in the B2B shipping industry.

Technology companies also dominate the stock markets. If ten years ago there was only one tech company in the Top 10 companies with the highest market capitalization, now they occupy half of the list, and most have a platform strategy, which leads to much higher performance and efficiency. On the strategy palette, this is a Shaping environment in which firms orchestrate an ecosystem of companies.

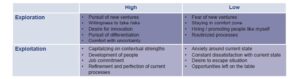

Exploration and exploitation in business

Big players tend to think that the game in their industry is well defined and it’s all about winning that game; small players believe they will reshape the industry. These two attitudes fit into the exploitation and exploration framework developed by James March in 1991.3 Exploration is about what’s new, search and discovery. In such organizations the focus is on long-term initiatives and projects, innovation and growth, and the culture promotes outward-orientation, flexible adaptation and empowerment. Exploitation is taking something that exists and making it better. Here the focus is on the short term, efficiency and productivity; the company is inward-facing, with an emphasis on discipline and clarity of direction.

The extremes of the two approaches represent the traps companies can fall into:

- Success trap, the “I am so good, I don’t want to change” mentality. Many successful companies neglect exploration and become complacent, bureaucratic and inward-oriented. They focus on their existing competencies and on delivering short-term performance, and they care too much about executive legacy. Kodak and Nokia, for example, got caught in this trap and failed – a fate that happens to one in three companies, according to BCG research.4

- Perpetual search trap, the “I like new ideas, I don’t want to spend time refining old ones” mentality. This often happens in small innovative companies that continually search for new ideas. A famous example is Xerox PARC, which spawned many innovations but failed to commercialize them (including the first PC mouse, which Apple went on to develop). To avoid this trap companies should engage in relevant innovations, define time horizons, select opportunities that fit their capabilities, use tactical experimentation and create external innovative platforms.

A recent study5 showed that only 2% of companies are ambidextrous – they efficiently balance both exploitation and exploration, live longer and are more profitable. They maintain exploitation business units while engaging in exploration activities through internal R&D departments, corporate venture capital structures or intense M&A activity. The latter is a more efficient way to integrate exploration, since scanning for and acquiring innovative new start-ups provides more flexibility and opportunities for better and more diverse ideas.

Exploration and exploitation – implications for leaders

Professor Jordan looked at the framework from the individual perspective. At the personal level, exploitation has been defined as reliability in experience through refinement, routinization, production and implementation of knowledge, while exploration refers to variety in experience through search, discovery, novelty, innovation and experimentation.6 Neuroscience has shown that different parts of the brain trigger each mode – one area is responsible for enhanced attention focus, while the other activates a search for alternatives.

Very few people are equally good at exploration and exploitation; they tend towards one or the other, which eventually affects individual behaviors and productivity. Explorers gain energy from going beyond their comfort zone, meeting new people, doing new things, learning new experiences and skills, battling the unknown. Exploitation-oriented people enjoy doing well what they know, are reluctant to leave their comfort zone and are process- and efficiency-oriented.

In addition to being aware of their own preferences, leaders should be cognizant of variations among team members. Thus different teams (exploration- or exploitation-oriented, or balanced) might be more suited to achieving different project goals (Table 2). Hence, leaders should think about their team composition, as well as what they are doing to stimulate exploration and exploitation in their teams. Exploration is stimulated by providing a secure base, nurturing curiosity and being comfortable with uncertainty; exploitation is usually motivated by focusing on “the now,” satisfaction with and commitment to the current state, and delivering the numbers.

Table 2: Influence of leader’s personal preferences on team

Key learnings

- Companies need to employ different strategies in different environments. There is no “one size fits all.”

- The main reason companies fail is they either focus only on exploitation (doing more of the same) or only on exploration (doing what is new). Both approaches are essential for success and need to be balanced properly.

- Most technology companies succeed because they employ new business models based on platform-type strategies that form a whole ecosystem of companies.

- Good leaders do not need to balance exploitation and exploration equally well within themselves; rather they should be aware of their own preferences and efficiently balance exploration and exploitation in the teams and organizations they lead.

1 Reeves, Martin, Knut Haanæs, and Janmejaya Sinha. Your Strategy Needs a Strategy: How to Choose and Execute the Right Approach. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2015.

2 Ibid.

3 March, James G. “Exploration & Exploitation in Organizational Learning.” Organization Science, 2(1), 1991: 71–87.

4 Reeves, Haanæs, & Harnoss. https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/growth-innovation-tomorrow-never-dies-art-of-staying-on-top/ 19 Nov. 2015.

5 Ibid.

6 Holmqvist, Mikael. “Experiential Learning Processes of Exploitation and Exploration within and between Organizations.” Organization Science, 15(1), 2004: 70-81.