Forty-five participants from 32 companies recently attended an IMD Discovery Event to find out what characterizes a high-turbulence environment, how to lead and drive change in the face of adversity, what organizational and personal capabilities are needed to succeed in turbulent times, and how to create and run an ambidextrous organization.

Turbulence can come about as a result of both external and internal factors. Some are cases of force majeure, such as natural disasters, acts of war or terrorism, while others are more commonplace, such as activity in the international commodity or financial markets, or changes in the geopolitical landscape, for example.

Internal factors leading to turbulence are mostly due to significant changes in company strategy, resulting from a deteriorating performance or M&A activity, for example, as well as internal seismic shifts as a result of leadership succession or cases of serious deception (like the Volkswagen fraud case). Very often companies experience turbulence both internally and from the external environment.

The rapid development and spread of social media amplifies the speed and magnitude of turbulence. A memorable example is Greenpeace’s successful campaign in 2010 in which it used a YouTube video to protest against Nestlé’s use of palm oil in its KitKat bar.

The Tunisian revolution in December 2010 is a good example of the effect of social media in the political sphere. In this case, social media did not cause the revolution, instead it accelerated it by enabling the protesters to share information and to coordinate protests.

In response to the increased role of social media, many organizations have special teams responsible for monitoring social networks in search of new ideas, trends and competition screening. In addition, they identify and respond to negative incidents and comments that could potentially threaten the company’s reputation.

What is turbulence?

Among the characteristics that distinguish turbulence from other critical situations are its large and uncontrollable scale, high velocity and fluctuation, its cascading effect and unclear patterns of evolution, leading to a chaotic situation.

It is commonly accepted that today’s organizations (in both the public and private sectors) operate in an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment (the VUCA world). Yet in times of turbulence, the situation quickly deteriorates and becomes explosive, full of conflict, insecurity and unpredictability, and people involved can become polarized and unreasonable. This leads to irrational demands that make no sense from a logical perspective, and leaders have to face strong and relentless opposition that could escalate conflict to the next level.

A leader is like a clown in a circus: he has the most important role of the whole performance, even though he has only one act to perform. He always knows what the plan is and what is going on, he stands behind the curtain throughout, and is always ready to come in if necessary and keep the show going.

The Tunisian revolution is also an example of the devastating effect of turbulence in the political arena. For 55 years Tunisia had experienced relative stability with only two president-dictators. In just three years of the Arab Spring, the country had three presidents and seven governments and suffered from political unrest due to high unemployment and poverty, and the permanent threat of terrorism. It was constantly under pressure from political parties, national organizations, as well as the media, for rapid improvement. In such circumstances, only drastic measures approved by political parties and major national organizations could have any positive effect. A new non-partisan, technocratic government was given a temporary mandate of one year to stabilize the situation, start implementing major strategic reforms to reduce chaos and improve economy, and prepare the country for new democratic elections.

A good example of turbulence in the business world is the crisis Air France experienced in October 2015 when, after over a year of bad financial performance, top management decided to implement a major restructuring plan by laying off 2,900 people. In just one weekend, union activists inflamed the situation to such an extent that following a board meeting on Monday a violent crowd of protesters attacked company executives, ripping their shirts and forcing them to flee over the security fence.

In such situations, the survival of the organization (or country) depends on its ability to rapidly respond to challenges and whether its leadership is a responsive and reliable point of stability for employees and other stakeholders.

A leader’s role in times of turbulence

In the VUCA world, stress and anxiety grow exponentially. To enable people to cope with this, a leader should give them autonomy and control about decisions relating to themselves.

In a high-risk, high-stake and highly insecure environment, the focus shifts to what is really important. The role the leader plays should be one of stability, he/she should be aware of what is going on, how the situation is developing on the ground and be ready to intervene only in case of problems.

In times of crisis, it is more important than ever to motivate and inspire others. Enacting real leadership during such times involves several important dimensions:

Figure 2: Enacting real leadership

Presence. While self-awareness is said to be a key element of good leadership, presence – a leader’s ability to stand in who they are and make that visible to others – is far more important.

Relating. A good leader is able to relate to others, to build relationships and find out what’s going on.

Sensemaking. In times of crisis, a leader is often faced with a range of varying opinions and perspectives about what is going on. He/ she should be able to take the information, make sense of it, create a direction and share it with others in a way that allows everyone to understand and follow.

Action. Once leaders have established their presence, can relate to others and make sense of the situation, they can then take action to drive things forward.

Service. The role of leader involves not only serving the organization, but also being responsible for others and acting in a way that ultimately serves all the stakeholders in that situation, whether internal or external.

Another essential element of leadership is trust. A good leader should be trusted and be able to trust others. Trust encompasses credibility, reliability, intimacy (the ability to make people feel safe and willing to confide), and self-orientation (the ability to focus on and care about others). Leaders also need courage – to take on the leadership role and necessary action – and to understand the power of common sense – putting a lot of clever people together in a room might not necessarily solve the problem.

Finally, leaders need resilience, especially in a turbulent situation. Resilient leaders are able to build resilience throughout the organization by putting the right people in the right places and stretching them just enough to get them out of their comfort zone and to achieve peak performance. Resilient employees are focused, energized and engaged and have a sense of wellbeing.

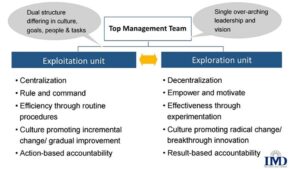

Ambidextrous organizations respond better to turbulence

A vast array of research has been done on the topic of ambidextrous organizational structures that combine the exploitation of existing capabilities and the exploration of new business opportunities (new customers, markets, products, potential disruptions). By nature, this type of organization is much better at coping with different challenges, particularly in times of turbulence.

Figure 3: Creation of an ambidextrous organization to drive change

Stora Enso, a leading global company in the paper, biomaterials, wood products and packaging industries, had traditionally focused on the production of pulp and paper. However, in 2006, it faced the challenge of rethinking its business in a drastically changing environment (urbanization, population growth, digitization, drive for ecological awareness and sustainability).

In order to shift from fighting for survival to playing to win, the company needed to focus on a number of key priorities. The first was to focus on the top, building diverse teams for truly novel perspectives, emphasizing the importance of inspiring and motivating people, and developing internal capabilities. It chose to empower its employees (Pathfinders/Pathbuilders), rather than external consultants, to address key business challenges, to implement the strategy shift and become change agents throughout the organization.

Until this point, Stora Enso had been set up as a traditional business organization, to exploit rather than to explore, so it had to decide how to transform to best fit the new strategic initiatives without harming its existing business. It deliberately added a new project-oriented network structure to its existing line organization, enabling the company to successfully transform itself from a traditional paper and board producer to a global renewable materials growth company.

The adoption of an ambidextrous organizational structure is not limited only to business organizations. The Tunisian technocrats’ government, whose mandate was to bring the country out of the chaos of the Arab Spring, was the first to apply a dual organizational structure to governmental institutions.

Alongside the usual ministerial line structure that was responsible for the daily operations of the government, a new exploratory unit called the “Government lab” was set up to lead innovative transformational projects. Enthusiastic and creative people were selected from different ministries and different levels, as well as the private sector, thus forming cross-ministry, cross-level collaboration teams working on the same projects. In this structure, open communication with the line organization regarding the purpose of setting up the Government lab was vital to reduce the sense of skepticism and threat of substitution within the traditional ministries. The new structure was successful in developing and implementing several major projects such as redesigning the national subsidy system, setting up a unique e-identification number for each citizen, and organizing the international conference “Invest in Tunisia, the Start-up Democracy.”

Key learnings

- In situations of high turbulence, survival cannot and should not be taken for granted.

- In times of crisis, leadership is about making hard choices, doing the unexpected, and sometimes the seemingly impossible, even in the face of opposition.

- In an environment of high turbulence, emotional resilience and “esprit de corps” are critical among the leadership team.

- Deciding on the information boundaries between the public and private spheres can be detrimental to your success.

- When you cannot anticipate everything (or even anything), you should trust your instincts, stick to your beliefs and stand by your values.

Tunisian turmoil: How a technocratic government brought order to chaos

On 17 December 2010, after a police officer confiscated the fruit and vegetables he was selling in the street without a permit and then being humiliated by the local administration, the 26-year-old Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire. This act of desperation sparked outrage since it represented many of the country’s problems: poor living conditions, corruption, lack of economic opportunity and a rigid, autocratic government. Within hours protesters came out onto the streets of Bouazizi’s town, and several days later the protests spread over the whole country, giving rise to the Tunisian revolution. In spite of President Ben Ali’s efforts to stop the protests by sending in special police forces, chaos continued to engulf the country, in part thanks to social media, which enabled protesters to share information and coordinate the protests. Riots soon spread to the capital Tunis, culminating in a national strike and mass demonstrations, and less than a month after Bouazizi’s act of protest, President Ben Ali fled with his family to Saudi Arabia.

The crisis came to a climax in 2013, following the assassinations of two prominent politicians, and later that year a transition government was formed consisting of non-partisan ministers, including six Tunisian expats who had been living and working abroad for many years.

The mission of the technocrats’ government was four-fold:

- To finish the democratic transition in Tunisia within one year by putting in place the State institutions, as stipulated by the new constitution.

- To organize and run free and credible parliamentary and presidential elections, and commit not to run for the elections.

- To initiate reforms to improve the macro-economic situation and create an investment-friendly climate.

- To restore the country’s security amidst a volatile and complex regional and international environment.

The new government was able to develop several big projects, such as redesigning the national subsidy system – withdrawing the widespread subsidies and focusing on targeted benefits for poor people – as well as defining a unique e-identification number for each citizen, making it possible to offer them better services. The projects also included reforming the higher education system, which included shifting the focus toward education for self-employment, formulating and launching the “Digital Tunisia” strategic plan, and organizing fair and free parliamentary and presidential elections to finish the democratic transition of the country.