In June 2012, some 200 members of the IMD Corporate Learning Network gathered for a special Discovery Event on leadership. For a day and a half, participants had a chance to network and to explore some of the emerging theories and practices of leadership development: how leaders need to react in a skillful and mindful way to situations as they emerge instead of relying on behavioral toolboxes.

Two contrasting views fuel debate in leadership theory and practice: The classic behavioral approach assumes that developing leaders means focusing on the person, his or her skills and experience, whereas the mindful approach holds that leadership happens in the moment and requires making sense ofthe evolving dynamic between person and context. In essence, training leaders in the behavioral tradition means providing them with a toolbox of knowledge and skills. But is this sufficient, given the complexity and human dynamics involved in leading people in organizations?

Every situation and moment is different. This is why mindful leadership emphasizes two much broader skills. The first is as old as Greek philosophy: know yourself. What roles do you play? What masks do you wear? How do you define your authentic self? The second is: read the context. This means skillfully interpreting what goes on for other people while it’s happening. Understanding what they might be thinking and feeling, and why. Understanding why they think and feel and behave the way they do. In a business context, reading the context correctly requires increasing skill as the work becomes less tangible: on the factory floor, managers can make objectively rational decisions given the concrete inputs and outputs. However, as managers move up in the organization, they must grapple with the ambiguity embedded inthe complexity of the executive role.

The work of senior executives revolves around making choices in these complex contexts. One of the dangers for senior executives as they struggle to align on ambiguous targets is getting stuck in unconscious behaviors, scripts, routines and patterns. Their focus narrows to making things happen, to churning out decisions and judgments. They forge ahead, overcoming resistance. This leaves little room for mindful leadership. The most effective leaders know that interpreting and sense making areas important as action. They stop and notice things. They pay attention to how people are saying something, not just their words. Using the metaphor of the iceberg, Professor Ben Bryant explains that moving from mindless to mindful leadership means becoming aware of what is hidden under the waterline. For leaders who function on auto-pilot, this implies stepping back and learning to see the subtle and often unconscious dynamics that determine the outcome of a situation.

Mindfulness in practice

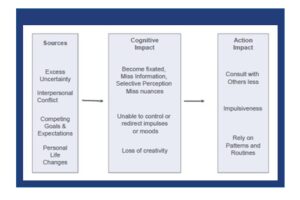

Faced with overwhelming demands and competing constraints, managers struggle to maintain focus and energy. Life becomes a never-ending inbox. They fall into a cycle of mindlessness that goes from impulse to action, bypassing a crucial phase of noticing and interpretation. In this cycle, impulsiveness is a way of discharging unpleasant emotions –firing off a testy e-mail, making a snap decision. There is safety in “doing” rather than “being.” Organizational pressures tend to push managers into constant action orientation.

For obvious reasons, impulsiveness does not offer the best results in terms of performance. It narrows our perception, clouds our acumen and leads us into repetitive behaviors. Cognitive busyness makes us oblivious to critical clues and signals: for example, missing signs that the team is not really aligned or that there is an unresolved conflict festering between important stakeholders.

The first step to internal mindfulness is becoming awareof our feelings, thoughts, impulses and body sensations. There is a big difference between feeling irritated and being aware that we are irritated. Achieving this subtle but essential shift in awareness is, in large part,a question of practice. Meditation is perhaps the most direct way of accessing a detached state in which we easily notice our thought patterns and sensations. Regularly taking 10 minutes to meditate allows us to become aware of what is going on inside us without judging it or suppressing it –a skill that is much rarer than we tend to believe: managers, after all,are paid to make judgments all day. Another useful tool in the search for mindfulness is a vocabulary of feelings. We tend to be highly unimaginative in the way we describe emotions. What do we mean by “I’m OK”? Bored, enthusiastic, fearful, excited, satisfied, confused? Developing a wider spectrum of words and descriptions for positive and negative emotions allows us to acknowledge their existence and their impact on ourselves and on others.

The second step is to be mindful of the key feelings and thoughts that are relevant to leadership. This includes our need for control, our need to protect ourselves, our search for safety, and our need to trust others. Why is this important? Because leadership is about working with others, building trust, developing the confidence to act, achieving alignment, implementing change and creating organizational culture: all highly emotional endeavors.

Leadership and authority: Our need for control

For many years, leadership styles theory dominated the field of leader development. According to this model, leaders could manage by consensus, participation, involvement, consultation or autocracy. The key differentiator of the styles was authority: how was authority used and shared between the leader and the followers? As new company structures emerged in the late 20th century, leadership theory evolved to explain so- called flat and matrix organizations. But these explanations still rested on a traditional view of formal authority vested in a specific individual, “the leader.” In reality, authority is a fluid and complicated social phenomenon. Models of leadership, such as autocracy or consultation, are too simplistic to reflect this.

One of the keys to understanding mindful leadership is widening our definition of “authority.” We may have contractual authority (to sign an invoice or approve a decision), expertise (we are an authority on a subject) or social gravitas (which may be based on demographics, personality and so on). Authority is not just a title, it is something that is intuited, felt, tested – it is a property of the social. Authority emerges every time a group of people comes together. It is as subtle as the impromptu seating arrangement in a board meeting, the “airtime” people get in conversation or the casual way someone consults his e- mails while a colleague is giving a presentation. People can give us authority and they can take it away just as quickly. It is an evolving dynamic. In a leadership role, we may “authorize” ourselves and we may also “de-authorize” ourselves (for example by minimizing our expertise or canvassing approval before taking any action). In an adaptive era, it is essential for leaders to understand the sources of their own authority.

Learning, defensiveness and resilience: Our need to protect ourselves

Taking up leadership in an organization tends to be an isolating experience, a mix of increased pressure, independence, responsibility and exposure. To cope, leaders develop a sophisticated array of psychological defenses. These protective mechanisms range from the conscious to the unconscious: humor, representation, suppression,rationalization,displacement, projection and denial. They are highly useful, but their downside is that, over time, they distort our perception of reality. They also stop us from learning and changing. They lock us in.

Each of us has two opposite tendencies: to be a “learning person” or a “defensive person.” A learning person has robust self- esteem, good self-knowledge, is autonomous and emotionally independent. A defensive person, in contrast, has either low or inflated self-esteem, holds many self-misconceptions, and is emotionally dependent or counter-dependent.

Mindfulness is also one of the five elements that assist managers in developing resilience –our ability to overcome personal difficulties, setbacks and turbulence.

Being a resilient person does not mean never feeling exposed or vulnerable. In fact, great leaders know that vulnerability is embedded in many actsof leadership. The first of these acts is initiating: being the first to speak,to reach out to others, to make a proposal or take a stand on an issue. There is always a risk of non- reciprocation. Leaders have to deal with rejection, often in visible or high-stakes interactions. Taking up authority also makes leaders vulnerable. Holding a position of authority implies tolerating loneliness, derision or being misunderstood. In the end, the courage to take up leadership and make the “first move” is based on acceptance of self. This requires acceptance of our imperfections. No one is perfect, not even iconic leaders.The question is: as a leader, should you allow others to see that you are vulnerable? The short answer is yes, but be selective about what vulnerabilities you show. In other words, as the HR director, you may reveal that you have no artistic ability, but admitting “I’m hopeless with people” is a very efficient way to de-authorize yourself.

Realistic Optimism: Even in dire situations, resilient leaders balance a realistic assessment of their predicament with an optimistic drive.

Action and Experimentation: Faced with adversity, it is important to keep momentum by staying active and experimenting with different solutions.

Being the Container: It is a natural human tendency to project our hopes, fears and emotions onto our leaders. Resilient leaders know that they must “contain” these projections without always reacting or taking them personally.

Mindfulness: Creating the mental space to really notice their thoughts, emotions, as well as the deeper dynamics at play around them helps leaders be more grounded and perceptive.

The Search for Meaning: Human resilience is closely linked to finding purpose and meaning in life. This search involves balancing periods of safety and predictability with periods of learning, vulnerability and growth.

Reading group dynamics: Our search for safety

The capacity to “read”and make sense of group dynamics is a critical skill for mindful leaders. Leadership, after all, does not happen in a vacuum. It is enacted in the interplay between leader and followers. It is a group phenomenon. Developing adaptive leadership involves shifting our view of group process from the classic model developed at Harvard to a more dynamic view that encompasses the group’s unconscious dynamics and behaviors.

The Harvard model of group process is based on three interlocking elements: inputs (group composition, shared task), process (share information, generate options, make decisions, take responsibility, control, learn) and outputs (decisions, action points, individual rewards and recognition). The underlying assumption is that groups behave in a rational manner. However as Nietzsche famously observed: “Insanity in individuals is something rare … but in groups, parties, nations and epochs it is the rule.” Groups are unpredictable. People’s behavior in groups is highly complex because there is an underlying, unconscious search for safety. Decoding the dynamics is an exercise that requires a mindful approach to understanding the constant search for safety.

There is a set of unconscious human paradoxes that influence choices and outcomes of leadership activity. Leaders need to be mindful ofthose tensions. As individuals we seek freedom and autonomy, and sometimes we need to control others in order to obtain that freedom and autonomy. However, we must also give up part of this freedom to belong to the group. While we need safety, this urge to feel safe can override rational objectives. As humans we have a strong need to belong and feel included, but belonging to a group means excluding others. These fairly universal paradoxes drive people to behave in outwardly mad or irrational ways in groups. However there is method in the madness – these behaviors express a deep ambivalence in meeting contradictory needs.

Keys to mindful leadership

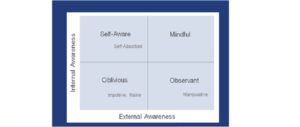

Mindful leadership is a constant balancing act. It requires holding in balance four sets of contrasting skills:

The first is to find a balance between expressing different parts of ourselves, our assertive side, our confronting side, our funny side, our compliant side, while remaining authentic. We naturally show different sides of ourselves as we move from one environment to another and we can also hold multiple roles at the same time. Successful leaders know how to express different parts of themselves.

The concept of role has broader social importance because it helps us relate to each other and differentiate ourselves functionally in order to achieve agoal. The problem with roles is that people often get stuck in them in each environment, and this in turn gets the entire group stuck in a dysfunctional pattern.

Expressing different roles can create surprise. This keeps followers on their toes by being unpredictable at times. By expressing their different selves, leaders help organizations stay alert and renew themselves. The trick is to show distinctive features that are genuine and that reflect the context in some way. In other words, the point is not to shock people for the sake of shocking them. There has to be a point, an underlying message. Leaders need to understand people’s expectations. They need to conform enough to adapt to their environment and surrounding culture: be different, but not too different.

The second centers on balancing emotion: how leaders need to accept the inherent vulnerability in their role, yet master emotional containment. Taking up authority and responsibility puts leaders in a highly exposed position. Their decisions are examined. Their behavior is scrutinized. Their performance commented on. Leaders are expected to take the initiative and be gregarious, yet they must often face rejection. They are vulnerable. This requires important reserves of inner strength. Professor Ben Bryant asks leaders: when should you show the depth of feelings and responses to vulnerability and when should you contain them? Most of the time, leaders need to “be the container.” It is natural for a group to resent authority, to panic in times of uncertainty and to express conflict in ambiguous situations. Leaders need to accept and absorb these emotions without fighting back every time.

Social distance is another skill that successful leaders excel at. All relationships unfold on a scale of closeness and social intimacy. Followers naturally seek to bridge the distance and become close to the leaders they admire. They are attracted to empathetic leaders who see them, who understand and respond to them. However, effective leaders know that they must also confront people, enforce boundaries and express their opinions honestly. This means giving people both high supportand high challenge.

The fourth skill in mindful leadership is balancing “noticing” with “focusing.” While much leadership advice suggests that we should focus on a goal, we should also not forget to notice from time to time. To notice means tobe mindful.

The final key to adaptive leadership is both simple and complicated: it is about who we are,our identity. Identity, like personality, is the part of ourselves that is more predictable and stable. But unlike personality, our identity continues to evolve over time.What makes you the person you are today? What were your formative experiences, your role models, your goals, ambitions and moments of compromise? In short, what sense can we make of the choices we have made, and why we made them. Without understanding our identity, where we have come from, and what we are, it is harder for us and others to know where we are going.