Many companies, even traditional ones, have entered a process of continued internal and market transformation through innovation. Think of the announced revolution in the automobile industry with electric and self-guided vehicles, or in banks with mobile banking applications. The acceleration of technological changes and the emergence of new business models often require a radical rethink of processes and even entire organizations, as well as a change in culture.

This concurrence of several change factors can be summed up by the acronym VUCA (for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous). The speed at which globalization and digitalization are proceeding in most industries is adding an urgency dimension to these necessary mutations.

Board directors are not just witnessing the acceleration of everything in the company they govern. They are in the midst of it, given their mission to support the company and its management throughout this ongoing metamorphosis. As a consequence, directors are bound to ask whether the CEO and the C-suite are on top of it as a team. Do they have the right leadership profile and the required multi-faceted and complementary competencies, individually as well as collectively?

This is a legitimate question that many boards may not feel fully equipped to answer. In the past, boards have always felt responsible for the selection, hiring and evaluation of the CEO, giving him/her a free hand to choose colleagues for the C-suite. Today, directors should ask whether the whole C-suite, not just the CEO, is prepared to deal with the necessary transformative challenge.

Indeed, today’s technology and business environments exert huge pressure on the top team to contribute a variety of complementary skills, attitudes and leadership profiles. The CEO alone is unlikely to be able to cover all the required talents. He/she is expected to orchestrate a diverse team and to ensure that each member focuses on some of the tasks that, combined, will bring about the necessary transformation.

Is your CEO a fixer? Or a grower?

Traditionally, the task of selecting and hiring a CEO involved responding to fairly straightforward questions. Does the company need to be streamlined, restructured, reorganized? Is its performance unsatisfactory compared to its peers? Or does it mainly need continued expansion into new market territories, either organically or through mergers and acquisitions (M&As)? This dilemma led boards to focus their search on what best-selling management author Robert Tomasko called either fixers, in the first case, or growers in the second.

The profile of these two CEO types was relatively easy to define. They were generally hired on the basis of their track record, either within the company or with their previous employer. In a way, many CEOs could easily fit either of the two labels.

Since companies tend to experience performance waves, fixers were often required to come and “clean the house,” or at least stabilize it after a period of fast growth. Similarly, growers were brought in to breathe new life into technologies and markets after a period of successful restructuring or performance improvement. This kind of changeover between fixers and growers has marked the history of many large companies. It is in this spirit that the board of GE chose Jeff Immelt – a presumed grower – after the departure of Jack Welch, a remarkable fixer.

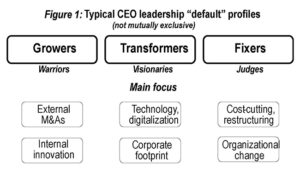

To help boards go beyond these basic types – fixer or grower may be too rough as descriptors – a typology of leadership profiles could be useful. As with all typologies, it may appear overly simple and incomplete. However, it has proved to be intuitive and easily grasped by all kinds of leaders. It can be applied to the CEO as well as to C-suite members because they often complement the profile of the CEO. This typology may also be applied internally to the board itself and its various members, who may include both fixers and growers. This can be done during one of the board self-evaluation retreats which, besides being fun, can prove very instructive.

A typology of leadership profiles

The generic typology of leadership profiles proposed by Robert Tomasko was covered in my book on innovation governance. It is summarized below.

Leaders, Tomasko advocates, need to develop four complementary abilities:

- To be aggressive, like a warrior

- To be conserving, like a judge

- To adapt to situations and people, like a diplomat

- To support people and ideas like a mentor.

The ideal leader would be that balanced individual who has these four abilities in equal proportions. But such leaders rarely exist! Real leaders tend to privilege one profile – their major – often with one (or two) complementary styles – their minors – depending on the tasks at hand and the company circumstances.

The warrior profile

Warrior leaders are eager to lead their troops into tough challenges, like entering new markets or pre-empting competitors in new technologies. In a nutshell, their philosophy is: “To be successful, let’s make things happen, and be fast.” They are at their best when they have the opportunity to take charge and show initiative. As dynamic and optimistic personalities, warriors tend to be practical, confident, persuasive, risk-taking and forceful. Some of these traits, if carried too far, can lead them to adopt utilitarian, arrogant, coercive, gambling and even domineering attitudes. In this sense they may be less good at delegating and winning cooperation from all in the company, but they create excitement.

The judge profile

Judge leaders like to work through processes, to rationalize and standardize. Their philosophy can often be captured as: “To be successful, let’s base our decisions on facts.” They are at their best when analyzing and weighing up options before acting. They care about always delivering what they promise. As concrete and rigorous leaders, they are factual, economical, tenacious, thorough, sometimes reserved, and always detail-oriented. But again, these traits sometimes comprise excesses. For example, to some people, they may appear unimaginative, stingy, rigid, perhaps somewhat dull, overelaborate and too data-bound. This explains why they may be perceived as less prepared to react quickly to unplanned environmental or market changes and to improvise solutions. For judge leaders, the “analysis/paralysis” syndrome may be a reality.

The diplomat profile

Diplomat leaders believe that progress will be achieved only if consensus and win-win solutions prevail. Their philosophy is: “To be successful, let’s ensure everyone gets a fair deal.” This attitude makes them quite effective in pursuing trade-offs and handling cross-functional or departmental conflicts. Their profile helps them achieve their objective because they tend to be flexible, experimenting, tactful, patient, socially skilful and shrewd. But, once again, the excesses of their traits – they may be seen as inconsistent, speculative, overcautious, indecisive and even manipulative – reduce their ability to force a decision or stick their neck out in an open conflict.

The mentor profile

Mentor leaders believe in the power of staff development and the creation of a positive work environment. Their philosophy is: “To be successful, let’s motivate and mobilize all our staff behind our objectives.” Their “soft power” orientation makes them considerate, somewhat idealistic, supportive and responsive. They may even be seen as modest. They are therefore at their best when working with others to improve the social climate within the company and to create and develop teams. But their critics sometimes call them gullible, impractical, unimposing, paternalistic and even passive. Their internal focus may make them less prepared to look outside and engage in competitive battles.

Clearly, all these profiles are needed in a top management team because they represent complementary leadership facets. As Preston Bottger, an IMD faculty colleague, stated: “Leaders do or cause to be done all that needs to be done, and is not being done, to achieve what we say is important!” When they work together, these diverse profiles contribute to providing a sense of purpose, direction and focus, as well as to building alignment and obtaining commitment.

What is the leadership profile of your CEO?

Let’s now revert to CEOs and characterize the leadership profiles of the two types – fixers and growers. Let’s also propose that a third type of CEO is needed – transformers.

The CEO as a fixer

Fixers tend to have a rather well-defined leadership style. Although there may be different variants of fixers, they can often be characterized as having several of Tomasko’s judge personality traits. Because of their down-to-earth attitude and trustworthiness – they hate uncertainty and like to deliver what they promised – fixers are highly appreciated by boards who generally hate unexpected (bad) surprises. As judges, fixer-type CEOs tend to focus alternately, or in parallel, on two main fronts:

- Radical cost-cutting and/or restructuring, generally for performance improvement.

- Organizational change, as a consequence of their cost cutting or to better adapt the company to its globalization or market challenges.

Of course, leadership cannot be reduced to a single dimension. So, fixer CEOs may share some of the traits of the three other profiles, and this will generally reflect their preferred mode of operation. Some of them – let’s call them judges/warriors – will go through their change campaigns in a fairly tough, not to say brutal, style. “Chainsaw Al” (Dunlap) at Scott Paper was one of the best known leaders in this group, hence the nickname that made him proud. Others may be more inclined to adopt softer more diplomatic or participative approaches; they may be characterized as judges/diplomats or judges/mentors. But in all cases, they remain intrinsically fixers, dedicated to streamlining their organization and/or their company performance.

The CEO as a grower

Whereas fixer-type CEOs are primarily focused on the internal functioning of their company, grower CEOs are more interested in exploiting opportunities in the external world. They want to grow their market and expand the company’s footprint. Their more externally aggressive style makes them closer to Tomasko’s warrior profile.

As mentioned earlier, boards appoint grower CEOs when they are dissatisfied with the company’s lack of growth. Whereas fixers are highly appreciated by bankers, financial analysts and shareholders, growers may create excitement in the media, and ultimately with shareholders, particularly if they adopt new technologies, open new markets or launch new product categories.

Growers may focus on the two complementary growth strategies to different degrees at different times:

- External growth, i.e. searching for the best opportunities available through complementary M&As.

- Internal growth, i.e. developing their company’s creative capabilities and processes around home-grown innovations.

Warrior growers may have different modes of operation, reflecting their personality. The more careful ones may combine their warrior profile with strong judge overtones. Others will adopt a diplomat stance to advance their M&A agenda, or a mentor sub-profile to mobilize their organization behind their growth-through-innovation objective.

The CEO as a transformer: An emerging phenomenon

CEOs who created entirely new industries have always existed – think of Edwin Land at Polaroid or Bill Gates at Microsoft. But the new-economy revolution has seen the multiplication of a completely different breed of entrepreneurial CEO.

Convinced of the need to move fast, pre-empt competitors and grab new market opportunities, they have capitalized on e-technologies to create entirely new industries or radically new business models. These strong and visionary personalities, from Amazon’s Jeff Bezos to Tesla’s Elon Musk, have captured the imagination of venture capitalists and analysts with their stated ambition to transform the world, and in their mind this is not an empty statement. But these new industry captains are not found only in the tech sector. Some, like IKEA’s Ingvar Kamprad, have built empires in traditional industries. Others have dramatically changed their company’s footprint by divesting entire lines of business and developing new ones, like Lou Gerstner at IBM, or by entering into bold alliances, like Carlos Ghosn at Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi. All these CEOs can be characterized as transformers.

The arrival of this new type of leader brings us to review Tomasko’s four leadership profiles and add a new one: the visionary profile/style. Visionary leaders see opportunities in all manner of external changes. Their philosophy is: “To be successful, let’s create a totally new future.” They tend to be curious, bold, unorthodox, passionate and, in all cases, determined. In short, they are at their best when they can challenge the industry, technology and market status quo. Their possible flaws – some may be overly inquisitive, forceful, impractical, emotional and even obstinate – may make them less at ease with the day-to-day handling of concrete implementation details. This explains why they are sometimes obliged to hire a strong and practical N°2, as Steve Jobs did with Tim Cook at Apple.

Transformer CEOs typically focus on different priorities depending on the situation and maturity of their industry. Their focus can take many forms, but at least two seem to prevail:

- The exploitation of new technologies – including digitalization but also new materials sciences and biosciences – to revolutionize their industry.

- The radical alteration of their corporate footprint by expanding their business and/or introducing totally new business models.

Like fixer and grower CEOs, transformers have complementary profile; their visionary attitude is often complemented by an aggressive warrior style. They more rarely adopt Tomasko’s three other profiles, particularly the judge. This explains their need to hire strong COOs or CFOs. Similarly, because of the aggressive way they pursue their goals, they lean more toward the warrior than the diplomat. And their sometimes abrasive personality – think of the late Steve Jobs’ reputation – doesn’t induce them to behave like mentors!

The board’s dilemma

In theory, all board directors should be aware of the type and profile of the CEO they have appointed to run the company and, above all, to acknowledge and understand why they have done so. This is in theory only, because personalities are complex and leadership profiles may present a number of gray areas. Actual CEOs may not fall easily into any one of the boxes in Figure 1. Most CEOs – usually the most effective – develop complementary styles, straddling several boxes depending on circumstances and their business requirements.

Nevertheless, the board would be wise to reflect on the profile of their chosen CEO – possibly in his/her presence – and the extent to which this profile is effectively complemented by other C-suite members. This review can be achieved by raising the following questions:

- If our CEO is primarily a fixer, who are the growers in the management team? Do they understand the importance of their countervailing responsibilities?

- If our CEO is primarily a grower, who is going to ensure that the deals, alliances and projects launched make economic sense and are rigorously managed?

- If our CEO is not fundamentally a visionary transformer, how can the C-suite, as a team, launch a collective effort to introduce radical change and start a transformation process?

- In sum, do we have a balanced profile of leaders in our C-suite – balanced in terms of competencies, profiles and focal points – to support our CEO in his/her innovative transformation of the company?

The last question is essential because the board should be prepared to fight the tendency of some executives to appoint leaders with whom they feel comfortable. It is indeed quite natural to surround oneself with people who share the same beliefs and values. Warriors love to be supported by highly dynamic warrior-style colleagues, and judges by rigorous fact-oriented judge-profile subordinates. Diversity of profiles in a top management team does not always come naturally!

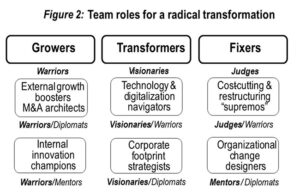

Radical transformations typically require a broad range of talents

Whatever their origin and purpose, radical transformations are likely to put a lot of pressure on the top team, who have to manage the transition while keeping the business viable during the change. This is why they often require ambidextrous leadership. Former IMD dean, Derek Abell, characterized it as mastering the present while pre-empting the future. Since few leaders would claim to be equally inclined – or talented – to cover both objectives, in practice this means that the top team ought to include transformers, as well as growers and fixers.

But, underneath, there are quite a few roles to be played if all the changes are to proceed in parallel. Figure 2 summarizes these key roles and highlights the possible leadership profile of the various players.

- In the transformer category, technology (and digitalization) navigators should be available to propose a roadmap and lead the various implementation projects. Similarly, corporate footprint strategists will need to devise how the new activities and new business models will compete in the market, and what to do with the old ones. These roles require a visionary attitude on both sides, complemented by practical considerations.

- In the grower category, marketing-oriented growth boosters and M&A specialists will be needed to define how the company can quickly gain access to the market, be it organically or through complementary supportive acquisitions. And simultaneously, all the creative energy of the organization will need to be harnessed by innovation champions to ensure the new products and services become winners. These growth boosters and innovation champions are likely to have strong warrior overtones.

- In the fixer category, it will be important to appoint a leader of the many cost-cutting and restructuring jobs that will inevitably accompany the change from the old world to the new. An organizational change designer will also need to propose and structure the new tasks and teams for implementation. These roles require a diversity of leadership profiles.

In summary, even though boards are unlikely to become involved in all the steps that will lead to the transformation, it would be wise if they made sure that all these roles are properly recognized by the CEO and C-suite, and adequately filled. The success of the transformation depends on it.

Notes

Tomasko R. M. Bigger Isn’t Always Better: The New Mindset for Real Business Growth. New York: Amacom, 2006. , Deschamps J. P. and B. Nelson. Innovation Governance: How Top Management Organizes and Mobilizes for Innovation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014: 332-340., Abell F. D. Managing with Dual Strategies. New York: The Free Press, 1993 and 2010.