If the role of marketing was ever to bring about a balanced relationship between sellers and buyers, then in many industrial sectors it has failed to live up to that promise. Consider the following scenario.

our core product or service has lost its uniqueness: competition has copied your winning features and is underselling you by a wide margin. Your customers, once delighted with your innovations and quality services, are now only interested in your price. They view all competing offers alike and dismiss your claims to the contrary as just a hollow sales pitch, and a handful of large customers, who account for an increasing share of your turnover, are aggressively using their bargaining power to the detriment of your prices and margins. And, as if that wasn’t enough, your marketing has become powerless as no amount of persuasive communication and brand building can redress this imbalance of the bargaining positions.

Sounds familiar and close to home? If so, you’re facing a scenario best described as “commoditization hell”, a situation faced by many companies who have seen their control over prices disappear along with their brand equity and customer loyalty. Few marketers can escape this scenario with their shirts on.

Hence the question: Can you fight commoditization and win?

The answer for a growing number of companies is an affirmative one. Their managements have discovered profitable opportunities in redefining their core business and are offering their customers compellingly differentiated values – values that they are willing to pay a premium price for. These companies have thus found ways of countering commoditization.

The following examples illustrate how two companies have done just that.

- SKF, the world’s largest ball bearing manufacturer, has turned its extensive know-how in rotation technology into value-added services for manufacturing operations. Far from haggling over the price of commodity bearings, the company now helps its productivity conscious customers, such as pulp and paper manufacturers, to maintain their production machinery, reduce or eliminate downtime, and maximize plant yield. Many of these services come with performance guarantees that are offered on the basis of contracts that ensure continuity of supply and expert advice for plant operators, and long-term account retention for SKF. The company’s service business is today its fastest growing and most profitable division

- BASF, one of the world’s largest producers of industrial paints, has stretched out of its increasingly commoditized products into coatings for specialized applications, in addition to integrated coating systems and solutions. With the Integrated Paint Shop, an innovation in auto coating business, BASF offers to apply its vast know-how in paints to operate a car manufacturer’s paint shop, providing all coating products specified by the customer (including those produced by competitors) in addition to technical advice and logistical support. Under this concept, offered to an increasing number of car makers including DaimlerChrysler, Volkswagen and Ford, BASF is paid not by the volume of coatings used – the common practice in the industry – but rather by the number of painted car bodies that pass the quality checks. The Integrated Paint Shop innovation has been a highly profitable addition to BASF revenues.

The markets for bearings and coatings in which SKF and BASF compete are commoditized, and buyers have the last word. Unlike many of their rivals, both companies have chosen to refrain from becoming cut-price vendors, a strategy that would probably have won them a few additional market share points, but with significant erosion in their profitability. Instead, they have chosen to fight commoditization by becoming knowledgeable about the businesses of their major customers, and by using that knowledge to bring value-added products and services to their markets. The cases of SKF and BASF illustrate how a firm can bolster its customer value proposition to combat the corrosive effects of commoditization.

Value-Added Strategies

When all customers appear to look alike, and the firm’s value offer has a one-size-fits-all quality to it (both features of many commoditized markets), it is time to ask some fundamental questions: beyond the lowest price, what else do customers really value, and how could the present commoditized offer, products or services, beredefined to better respond to their often unarticulated needs?

To illustrate, in trying to learn what SKF industrial customers found important, SKF management discovered early on that even more important than the price of a ball bearing or its quality was the customers’ desire to minimize or eliminate machinery downtime, which could cost tens of thousands of Euros per hour of lost productivity. The company then realized that it could offer SKF’s top-grade engineering know-how to its productivity conscious customers as an add-on benefit, and also as a new source of revenue. Similarly, BASF learned that the main concern for its increasingly cost conscious auto paint customers was not the per kilo price of the paint, but the total cost of a painted body. So instead of haggling over the paint price, the company put its energies into finding ways of reducing the

customer’s total cost of coatings, in which the paint accounted for just a fraction. Such discoveries are the initial insights for redefining a vendor’s offer for more value to the customer, and greater differentiation and pricing discretion for the supplier – a true win-win outcome.

So what are the strategies that create added customer value and, in doing so, fight commoditization? To begin with, there are no quick fixes to the pervasive power of commoditization. As a permanent feature

of today’s marketplace, it will continue to challenge business organizations, even the best managed.

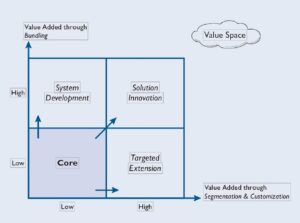

While there is no panacea, we can still identify at least three possible strategic trajectories, which could bring much needed differentiation to a commoditized core business. These generic strategies

are highlighted in the “Value Space” matrix shown in Figure 1 and explained below.

Let us first start with the two dimensions of the matrix: Segmentation and Customization, and Bundling. They reflect the ways a company could add value to a non-differentiated core product or service. By moving to the right along the horizontal axis, the firm is increasingly segmenting its current and potential customers and, in doing so, customizing its offers around the particular, and often unmet, needs of those segments. Along this axis, therefore, added value is created by more effectively meeting the requirements of the different customer segments or individual accounts.

By moving up the vertical axis of the matrix, on the other hand, the firm is augmenting its value proposition, beyond its core product, by “bundling” related or even unrelated products and services into a single offer. In other words, there is more to the offer than the commoditized core product, thereby allowing greater differentiation. The extra customer value that comes with bundling can be measured in the greater speed and convenience of working with a single supplier, a lower transaction cost, and a more complete quality assurance for the augmented offer.

The two value-adding dimensions described above lead to four possible combinations, identified in the matrix as Core, Targeted Extension, System Development, and Solution Innovation. The latter three pertain to value-adding strategies. To understand the significance of each of the four quadrants, they are further elaborated below.

- Core: This quadrant, low on both value-adding dimensions, is the starting point, where a company’s offer lacks sufficient differentiation to avoid the commoditization trap. Customers do not perceive compelling differences between the firm and its rivals. What is offered is not sufficiently adapted to the specific requirements of individual customers or their segments, nor does it have an added “bundled” value. Nevertheless, the firm may still attempt to bring a measure of vitality to its commoditized business through a combination of operational excellence (including incremental quality enhancement), and continuous improvement. A good example of revitalizing a commoditized core is that of Dow Corning. Recognizing that its mature silicone products could no longer be coupled with the company’s excellent service and sold for premium prices, Dow Corning created a separate business and a new brand, Xiameter, for selling through the web its commodity range of products to volume customers at highly competitive prices. The success of the ‘no-frills’ Xiameter illustrates how companies might de-bundle products from services, and reformulate their stripped down value proposition to profit from commodities.

- Targeted Extension: This quadrant represents a strategy that aims to add value by stretching the firm’s core offer into more segments, to better meet special needs. Under this strategy the firm may decide to pursue the dual tactics of offering the under-adapted core product to some customers, and the more targeted ones to others. Alveo, a European producer of polyolefin foams, has used this strategy to extend into diverse applications (such as wooden floor underlay, lining for shoes, cap seals for cosmetic bottles, and others) by customizing a standard foam product to the specific requirements of each segment. The extra adaptation has meant greater flexibility in pricing, with some of the more advanced applications carrying a price premium of 35% over the undifferentiated core product.

- System Development: Firms choosing to compete in this quadrant develop a package of products and services that offer the synergistic benefits of a “system”. The value added for the customer lies in the integration of the system’s constituent elements, so that the “bundled” whole is larger than the sum of its parts. SKF, for example, sells car and truck repair and replacement kits incorporating its core product, ball bearings, encased inside a sub-assembly such as a water pump, a clutch release unit, or a belt tensioner. In addition, the kits include accessories such as seals, nuts, and other tools for safe and rapid installation. Not all the bundled components are produced by SKF, many are outsourced. But the finished kit carries the company’s brand and performance guarantees.

- Solution Innovation: What happens when a firm’s offer consists of a full set of bundled products and services that are specifically targeted at certain customer segments or individual accounts? This is precisely the strategic scenario of the upper-right quadrant where value creation takes an ambitious turn away from the core business, and addresses specific customer problems with specific solutions – solutions that combine tangible products with highly focused intangible services such as technical advice, training, consulting, and the like. BASF’s Integrated Paint Shop package of products and services is an example of a solution innovation in the auto coating industry. Each package is constructed around the very specific requirements of a car company and a plant; it represents a one-stop sourcing of products and services, with significant savings for the customer. A firm planning to enter the solutions business needs to “think outside of the box” and reinvent what the industry has traditionally defined as value. Solutions strategy demands innovation in value creation. And it promises attractive margins.

Stretching Beyond the Core

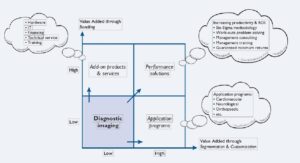

GE’s Healthcare division, one of the world’s largest makers of medical imaging products, is an example of a company employing multiple value adding strategies. While the company’s products, such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scanners, do not fit the common notions of commodities, the fact is that these core technologies are maturing. GE Healthcare has been active in finding new sources of differentiation and revenues along each of the three value added trajectories defined above.

As shown in Figure 2, imaging products have been extended towards increasingly narrow medical applications including cardiovascular, neurological, orthopedic, and vascular. Each focused extension consists of products and application programs targeting the specialists in the medical area. The company has also bundled its product offerings with a wide array of services in the areas of financing, information technology, technical service and training, just to name a few. The product-service package is meant to facilitate the acquisition, commissioning a routine operation of the imaging products by healthcare providers.

More recently, with the launch of Performance Solutions, a package of tailored services, GE Healthcare has entered the potentially lucrative consulting business targeting public hospitals and private clinics. The new offering provides a full range of services aimed at upgrading the productivity and operational efficiency of investments made in medical equipment. Expanding capacity and patient throughput, increasing revenue growth, and improving the return on invested capital all make up the customer value proposition of GE Healthcare’s solutions business.

Marketing Customer Success

If there is a single common denominator for all value-adding strategies described here, strategies that have a fighting chance to counter commoditization, that denominator is customer success. The added value and the differentiating power of each strategy lie in its attempt to reach beyond a traditional definition of the core product or service, so as to offer customers novel benefits that boost their success in their own business. Benefits include increased productivity, reduced cost, and general improvement in competitiveness.

The job of marketers in such demanding context must be multifaceted: understand key drivers of a customer’s business success, discover opportunities for new customer benefits, formulate strategies that deliver those added benefits, and then ensure effective strategy implementation throughout the organization. A tall order? Absolutely. But short of customer success as a guiding light for strategy and management action, any attempt to differentiate a firm’s products or services will be rightly viewed by the market as nothing more than marketing hype. And that’s no way to fight commoditization.