Seventy-nine participants from 50 companies attended an IMD Discovery Event that focused on the challenges involved in making strategic partnerships work.

Alliances and partnerships have always been part of human history in all areas of life – from private to public and from politics to business. Companies have worked with partners across countries, businesses or within their value chains for a variety of reasons, whether from a desire to expand or a need to cut costs. Yet, in recent years the growth of partnerships has accelerated, driven by the benefits of risk sharing and resource pooling, technology convergence, industry deconstruction (from linear value chains to industry value networks) and knowledge diffusion. The automobile and pharmaceutical industries in particular provide good examples of partnerships that have evolved from simple contingency and contractual relationships to more capability-focused ones.

According to a 2014 PwC CEO survey, more than 80% of US CEOs are currently looking for strategic partnerships or intend to do so in the near future.1 Nevertheless, in the last three years only around 65% of those seeking new strategic alliances have been successful.

What makes a partnership strategic?

In a strategic partnership the partners remain independent; share the benefits from, risks in and control over joint actions; and make ongoing contributions in strategic areas. Most often, they are established when companies need to acquire new capabilities within their existing business. Strategic partnerships can take the form of minority equity investments, joint ventures or non-traditional contracts (such as joint R&D, long-term sourcing, shared distribution/services).

Strategic partnerships inevitably involve challenges that have to be resolved efficiently to ensure the longevity and success of the alliance, such as isolating proprietary knowledge, processing multiple knowledge flows, creating adaptive governance and operating global virtual teams. If these challenges are not tackled, the partnership will more than likely fail, which, as the empirical research shows, happens in more than half of the cases.

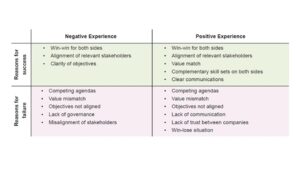

A short survey conducted during the event revealed that around 60% of participants had had a positive experience with strategic partnerships, while 31% had experienced a failure (9% had no experience). Reasons for success or failure included the importance of matching the objectives, values and relevant stakeholders, effective governance and the necessity for a strategic partnership to be mutually beneficial (see Table 1).

These results are in line with the empirical research, which identifies three major reasons for failure of strategic partnerships:

• Underinvestment: disagreement on revenue and cost sharing, lack of resources, lack of executive sponsorship and commitment, etc.

• Over-appropriation: coopetition, customer ownership issues, intellectual property sharing, etc.

• Misalignment: conflicting goals and incentives, unclear roles and responsibilities, difficulty in communicating the joint value proposition, extension of the internal silo mentality.

In order to avoid such failures and effectively build joint capabilities, strategic partnerships should be based on trust and follow five simple steps:

Strategize

Quite often strategic partnerships are formed to address the competitive threats of imitation and substitution, yet while the threat of imitation should be addressed in the value channel area, the response to substitution should lie in strategies at the business model level. In general, companies that decide to pursue strategic partnerships should introduce changes at the strategy level, including organizational structure, processes, and most importantly – commitment at all levels. Companies should clearly define the areas in which partnerships should be built based on its general strategy as well as its objectives.

Nestlé adopted a strategy change toward a partnership-based model in the areas of innovation and R&D in order to fight competition and imitation. Its in-house innovation system was no longer capable of sustaining annual growth of 5% to 6% and keeping up with the competition that was intensively using open-source innovation. In 2007 Nestlé’s organizational structure was a mix of functional/geographic/business divisions and did not allow for flexibility and efficiency in terms of managing strategic partnerships. In total 5,000 people were working in R&D within different business units, and only two people were responsible for partnerships. After mapping the

existing R&D expertise inside the company to identify opportunities for shared knowledge and expertise, as well as potential areas for open-source innovation, a special business unit was created that was responsible for all strategic partnerships. By 2009 Nestlé had developed a profound practice for strategic partnerships and had built a broad scope of alliances across businesses, universities, start-ups and venture capitalists.

Search, Screen and Select

One of the common mistakes businesses make when looking for possible partners is to consider only a few options instead of looking at the whole ecosystem of strategic partnerships. As a result, search, screen and selection processes remain decentralized and ad-hoc (except for the companies with developed capability and a history of successful strategic partnerships).

In general, companies should use a variety of mechanisms in their search for possible partnership opportunities, such as existing contact networks (suppliers, research partners), specialized industry organizations, associations and conferences. In the screening phase, companies should use strategic partnerships to acquire new capabilities within existing business, and be aware of consumer insights. They should also focus on limiting the number of growth areas and finding the right business champions in the areas of interest. The selection process should take into consideration a good match in terms of capabilities, competences and culture, as well as readiness to invest “in kind.”

NetApp applies a well-structured, systemic approach when searching for possible partners. The global IT product and services industry is diverse, with companies ranging “from one-stop shops” (big vertically integrated IT companies, such as IBM, Oracle and Dell, which provide the whole range of services) to small companies like NetApp that do business within one segment only.

In order to successfully compete with “one-stop shops” in infrastructure for cloud computing and provide its customers with the whole range of services, NetApp started looking at establishing strategic partnerships in adjacent areas of IT infrastructure. The first step was to map the competitive landscape across all areas of cloud infrastructure, distinguishing “best of breed” companies among the small specialized companies in each area. Eventually, it formed a non-equity partnership with Cisco, called FlexPod, which engages virtual teams consisting of best professionals from each company, and forms multiple small partnerships in various areas and countries.

Structure

There are multiple structures of strategic partnerships – from non-equity alliances, mostly in the form of non-traditional contracts (such as joint R&D, long-term sourcing, shared distribution/services) to equity-based partnerships in the form of minority equity investments and joint ventures.

The main reasons for choosing non-equity strategic partnerships are high uncertainty in the market, the existence of several possible partners (the rationale is to start loose and maintain competition between possible partners), the risk of damaging existing partnerships, and high organizational fit.

A joint venture is usually preferred when there are differences in culture and/or in the size of the companies (to minimize the risk of under-commitment by the smaller partner). Yet in order for a joint venture to succeed, it should recruit independent people to make a fresh start rather than engaging employees from both companies, who already have different cultures and conflicts of interest and who might prioritize the goals of their own companies rather than those of the JV.

Overall, joint ventures are the least popular form of partnership; they are the most difficult to manage and have an average life span of around seven years. According to McKinsey,2 many joint ventures fail because they spend more time on steps where less value is at risk (50% of time spent on negotiating deal terms, which constitute only 10% of value at risk) and less time on steps that have more value at risk (only 20% of time spent on business model and structure, which represents around 40% of total value at risk).

Following negotiations, the master agreement should be signed at the C-level (preferably CEO) and should explicitly summarize all the inputs and shared responsibilities and ownership of intellectual property, assets, etc., as well as conflict resolution and exit terms. Moreover, companies should avoid money investments by investing “in kind” (equipment, technology, people, buildings) to increase the commitment of both partners, because as soon as money is involved everything becomes a transaction rather than a long-term joint endeavor.

It is important to understand that all the aspects of negotiations, as well as the successful launch of a strategic partnership, are vastly affected by cultural values, such as individualism vs. collectivism, egalitarianism vs. hierarchy, high vs. low context. Such cultural and language differences can become the root cause for misunderstandings and conflicts, which can be diminished by mutual respect, awareness of cultural differences and misinterpretation of the other party`s behavior through your own cultural values.

In 2007 Starbucks tried to enter the Indian market through a joint venture with Future Holdings, but the venture failed due to problems with government approval as well as inside the partner organization. In 2010 the FDI regulation changed, allowing 100% of foreign ownership in Indian companies, and a year later Starbucks decided to repeat its attempt and partner with a big local company with expertise in dealing with local government and building a working supply chain. Tata, India’s premium brand, which had great market knowledge and was the largest coffee grower in India, was chosen as a strategic partner. At first, a non-binding open-ended Memorandum of Understanding was signed at the top level of both companies. However, five big issues needed to be resolved: equity stake, branding, pricing, growth pace and supply chain.

After intense negotiations, a JV was formed with an equity stake of 50/50 (signalling trust between partners). Each party compromised on some of its original positions to create a sustainable growth strategy. Starbucks was launched in Mumbai in 2013 and has since grown to other cities.

Start and Stabilize

Developing a supportive culture within the company is vital to ensure that a strategic partnership is efficient and productive. This means recognizing partnerships as a corporate priority (with inclusion in the corporate communication strategy). Support from senior leadership should be coupled with support from partnership leaders and teams.

Nevertheless, conflict is inevitable, especially in the early stages, and interest-based problem solving is the best way of tackling them. This requires separating people from the positions, emotional aspect from the rational issues, focusing on interests, generating mutually beneficial options, developing a contingency plan, and clarifying the commitment of both parties. Yet the most important first step is to identify and agree on the issues to be resolved. The contract should include a coordination aspect – an opportunity to revisit the contract, as well as conditions for escalating the issues, who should be escalating the issue, to what level, veto rights, and so on.

Study and Steer

Quite often, companies form a special unit (with a clearly defined role – pull vs. push) that is responsible for enabling and supporting strategic partnerships. These units usually hold a portfolio of strategic partnerships or projects within the partnership to make coordination more efficient, increase the scope of partnership and build up expertise. A portfolio approach to strategic partnership increases effectiveness since, according to BCG, the broader the scope for the partnership, the more successful it will be.

Such a coordination unit ensures brokering knowledge, legitimizing competence and institutionalizing organizational memory, as well as transferring best practices across its portfolio.

US-based Eli Lilly has a long history of successful strategic partnerships. Despite a high prevalence of M&As in the pharma industry, the company’s management decided to outgrow the industry by organic development and to leverage external capabilities through alliances. In 1999 it established the Office of Alliance Management (OAM), to build its capability to become the best in alliance management. All the external partnering activities were consolidated under three groups: the Research Acquisition group, which identified potential candidates, Corporate Business Development, which focused on the due diligence process and the negotiations, and the OAM, which supported the successful implementation of the alliance and minimized the risk of alliance failure for reasons other than scientific ones. OAM people participated in the due diligence and negotiation phase to ensure the deep understanding of the partner’s interests and business. By 2006, Eli Lilly had become a model within the industry for institutionalizing alliance capabilities within its organization, and over the years has become best in class in terms of partnering strategies within the pharma industry.

Key takeaways

With the significant increase in strategic partnerships, companies should bear in mind that success depends heavily on adopting a proper strategy, alignment (within the company and between the partners) and seamless integration into the organization’s processes and operations. Nevertheless, it is essential to focus on sharing commitment and competencies to create value.

Open communication lays the foundation for successful strategic partnerships, ensuring clarity of objectives, trust and strong relationships.

On the operational level, the most important group to involve, from both companies, is middle management since their objectives are often conflicting. Creating special mutually accepted metrics to measure the success of the alliance is also important.

When structuring the partnership, equity serves as a substitute for trust. If trust is weak, the partners tend to feel “it pays to cooperate,” whereas strong trust stimulates partnerships to the level of personal relationships, reflecting solidarity and similar cultural values.

References

[1] http://www.pwc.com/us/en/ceo-survey-us/2014/assets/2014-us-ceo-survey.pdf

[2]http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/corporate_finance/avoiding_blind_spots_in_your_next_joint_venture.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD Nexus. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/nexus