Does the bullwhip still strike?

Most operations and supply chain managers have been confronted with the “bullwhip effect”. The term was first coined by Procter & Gamble (P&G) to describe an occurrence observed in baby diapers. While end-consumer demand for diapers was relatively stable, P&G noticed a large variability in the orders placed upstream in the supply chain (i.e. to suppliers). Subsequently, the bullwhip effect has been defined as the phenomenon whereby demand variability is amplified upstream in the supply chain (from customer to supplier)[1] – see Figure 1.

The bullwhip effect is known to cause great inefficiencies and costs through excess inventory, lost revenues, superfluous capacity or poor customer service. For these reasons, the phenomenon has received strong attention from both researchers and practitioners for almost two decades. Hence, we now know a great deal of the factors that cause the bullwhip effect and what we can do to reduce it.

Over the past decade firms have made significant investment to counter the bullwhip effect in the forms of more elaborate IT systems and collaborative efforts. POS data sharing systems, Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) and Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment (CPFR) are examples of such programs. Various case studies have illustrated their success in increasing operational efficiency. So, where do we stand today? Does the bullwhip still strike?

The answer, according to our research [2], is a resounding YES! In a study of 15,000 firms over a period of 36 years we observe no significant decrease in the bullwhip effect over time. This is both surprising and worrying given recent company efforts. Have these efforts been in vain or are there additional factors at play that off-set any progress made over the years? One explanation might lie in recent trends linked to globalization and an increasingly complex market place.

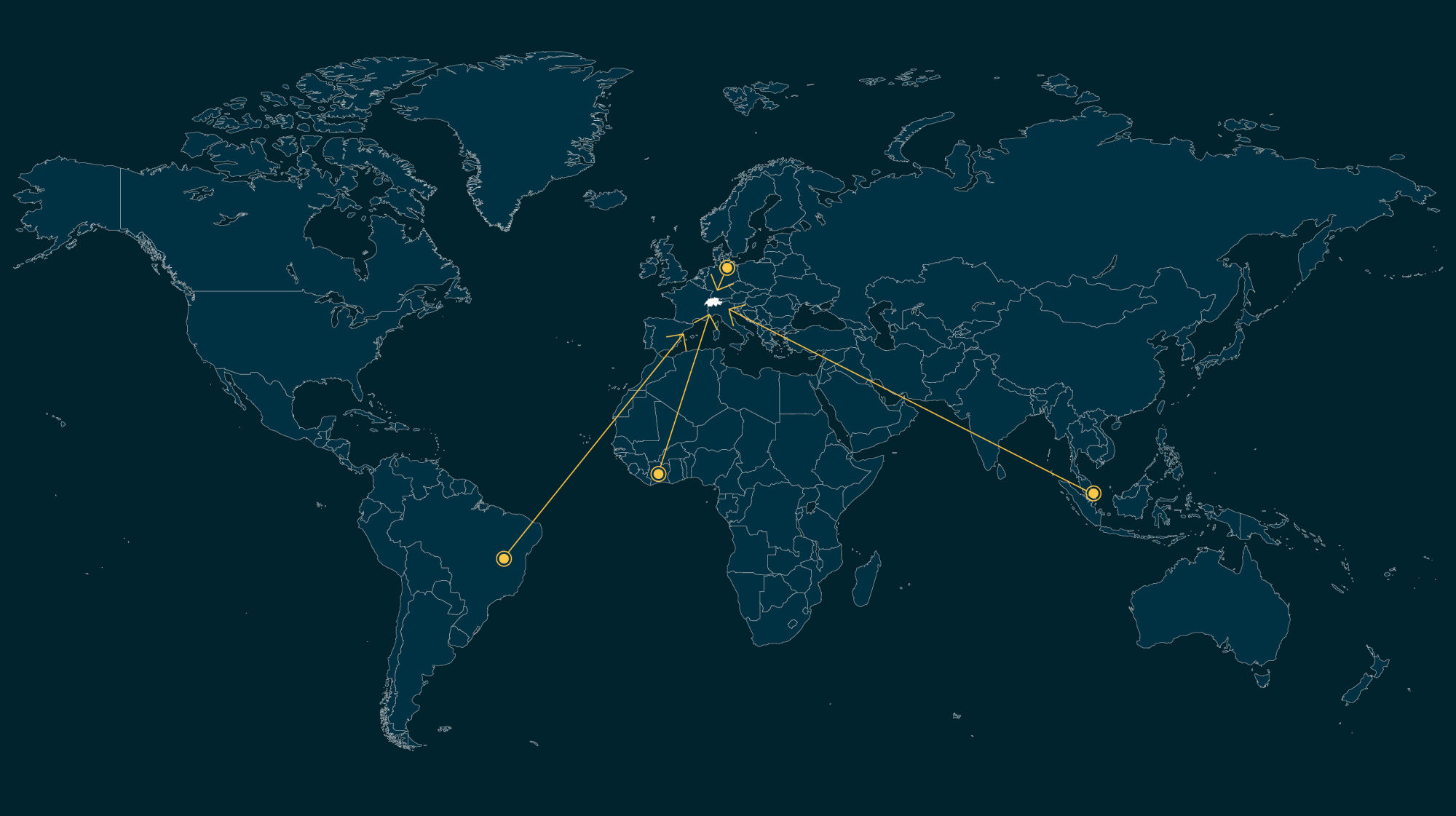

During the past two decades firms have been exposed to higher product variety, shorter shelf-lives and an increased dependency on supply chain partners[3]. Additionally, outsourcing is a widespread practice that increases lead time and limits the possibility of information sharing.

The good news is that not all firms bullwhip. The orders from the average firm to its suppliers are 90% more variable than incoming demand2. However, there are large variations across firms and industries, suggesting that it is indeed possible to dampen, or even quench the bullwhip. In general, firms that are further away from the end-consumer exhibit a stronger bullwhip effect. This supports the idea that a lack of demand visibility is an important underlying cause.

So, what can be done? In light of the aforementioned discussion, mangers need to take a step back and think about how traditional bullwhip mitigation strategies have been affected by recent trends. Practices such as outsourcing can reduce costs on the short term, but certain bullwhip mitigation strategies, like real-time information sharing, might be less viable with an overseas supplier.

In today’s global economy, margins are put under pressure and the supply chain, not the firm, is increasingly seen as the unit of competition. Although demand amplification to suppliers might not have a direct effect for the focal firm, it can rebound in the form of higher costs and a decrease in service and quality.

Overall it is important to keep in mind that:

- The bullwhip effect is still widely present and continues to cause great inefficiencies.

- Mitigation strategies to counter the bullwhip effect have been successfully deployed by some companies but risk being counteracted by recent trends that increase demand variability and supply chain complexity.

- This situation creates a trade-off which managers need to balance with care: On the one hand, recent trends can lead to reduced costs and stronger sales. On the other hand, the same trends can cause great inefficiencies and potential supply chain disruptions.

Operations and supply chain managers should continuously monitor if their company’s supply chain suffers from a bullwhip effect. Being well aware of it doesn’t mean that you have conquered it. All too often it is a moving target and detecting artificial demand variability instead of investing in more sophisticated forecasting systems or more manufacturing capacity may ultimately win the day.

Ralf W. Seifert is Professor of Operations Management at IMD and director of the Leading the Global Supply Chain (LGSC) program.

Olov Isaksson is Assistant Professor at Stockholm Business School, specializing in supply chain analytics and buyer-supplier relationships. He previously worked at Louis-Vuitton and Henkel as a supply chain project manager.

[1] Lee, H. L., V. Padmanabhan, S. Whang. 1997. Information distortion in a supply chain: The bullwhip effect. Management Science 43(4) pp. 546-558

[2] Isaksson, O. H. D. and R. W. Seifert (2015) “Quantifying the Bullwhip Effect Using Two-Echelon Data: A Cross-Industry Empirical Investigation,” forthcoming in the International Journal of Production Economics.

[3] PwC (2013), PwC and the MIT Forum for Supply Chain Innovation: Making the right risk decisions to strengthen operations performance, http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/operations-consultingservices/publications/supply-chain-risk-management.jhtml.

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Manufacturers must adopt a unified strategy across different divisions if they are to extract the full value of Industry 4.0.

The supply chain risk management literature differentiates between disruption risk that arises from supply disruptions to normal activities and recurrent risk that arises from problems in coordinating supply and demand in the absence of disruption...

Supply chain management experts Ralf Seifert and Richard Markoff pose the question: is fulfilment still an FMCG core competency?

The deadly blasts from tampered devices in Lebanon highlight the fragility of supply chains, making it clear that better security measures are urgently needed.

As society moves further into the digital age, emerging technologies bring unprecedented opportunities for economic growth, operational efficiency and societal advances. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing...

Companies need a new, holistic approach to sustainability if they are to head off criticism and accusations of greenwashing.

The mining sector's ability to produce the raw materials required for climate change mitigation will have significant supply chain implications, argues IMD's Carlos Cordon.

Demand Planning Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are frequently criticized for being too complex or irrelevant. However, an emerging approach is gaining popularity: evaluating the effectiveness of the planning process itself, rather than just the...

Turbulent times can leave businesses scrambling for measures to help them bounce back after disruption. But these actions may in fact increase overall supply chain fragility.

The sheer complexity of trade regulation and the risk of non-compliance mean companies are missing out on billions in tariff savings from Free Trade Arrangements (FTA) in their global supply chains. New AI tools can help remove some of the barrier...

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

in Production and Operations Management 16 November 2024, ePub before print, https://doi.org/10.1177/10591478241302735

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications