At an IMD Discovery Event, more than 200 industry leaders gathered to hear Professor Kohlrieser speak about resilience in high-performing leadership. Every manager experiences stress and adversity, but must be able to bounce back in order to meet new challenges. Professor Kohlrieser highlighted the importance of adopting the right mindset and coping mechanisms in order to restore leaders to their full potential and energy.

What is resilience?

Resilience is the human capacity to meet adversity, setbacks and trauma, and then recover from them in order to live life fully. Resilient leaders have the ability to sustain their energy level under pressure, to cope with disruptive changes and adapt. They bounce back from setbacks. They also overcome major difficulties without engaging in dysfunctional behavior or harming others.

Resilience is a crucial characteristic of high- performing leaders. Leaders must cultivate it in themselves in order to advance and thrive. They also carry the responsibility for helping to protect the energy of the people in their teams. Leadership is sustainable only if individuals and teams are able to consistently recover high energy levels. During the event, Professor Kohlrieser asked the audience: “How many of you have seen too much conflict in the workplace? How many of you have observed people getting sick or burning out?” A majority of audience members raised their hands, emphasizing the importance of fostering healthier human dynamics in the workplace.

The importance of resilience was brought into sharp relief here in Switzerland when two high- profile executives committed suicide over the summer of 2013. Both the CEO of Swisscom and the CFO of Zürich Insurance ended their days, partly as a result of toxic professional situations and working relationships. These men left behind families and children.

Self-leadership

A stunning example of resilience is Nelson Mandela. He was sent to prison as a young firebrand who believed in taking up violent means of resistance when the justice system failed. Twenty-seven years later, he came out advocating peace and reconciliation. During his long confinement, Mandela mastered the art of self-leadership. He took great inspiration in the poem “Invictus”, written by William Ernest Henley, which ends with the verses “I am the master of my fate/I am the captain of my soul.”

It is often forgotten that one must learn to lead oneself before being able to lead others successfully. Before take-off, flight attendants instruct that, in the event of a drop in the cabin’s air pressure, parents should put on their own oxygen masks before helping children with theirs. In a similar way, self-leadership provides the backbone for the effective leadership of groups. A high- performing leader needs to be physically, mentally and emotionally functional– as well as resilient– in order to inspire and guide others to achieve ambitious goals over the long term. The journey to inspiring others starts with “How do I inspire myself?”

The bonds that sustain

Resilience is about the whole person. As Professor Kohlrieser emphasized: “It is not enough to talk about the brain, we also need to talk about the heart. When people at work close their hearts and lose empathy, they lose an essential component of their leadership.” High engagement in teams requires passion.

It also requires people to have an open heart, to express feelings and to be curious about others. Leadership does not occur in an emotional vacuum – thinking and feeling individuals are part of the equation. That being said, it is critical to value both bonding and emotional autonomy. Bonding is essential, but leaders should avoid becoming emotionally or mentally hostage to others.

Resilience and Grit

Resilience is an essential element of the human quality known as grit. Gritty individuals work hard and persevere to achieve their goals. They are unyielding in the face of hardship. They are also extremely focused and loyal in their passions. They commit to their area of interest for the long term–they are marathoners as opposed to sprinters. The Grit Questionnaire, which participants in the IMD Discovery Event took, evaluates these two main elements: resilience to situations of failure and adversity, on the one hand, and consistency in pursuing specific interests, on the other. Research has shown that grit is highly predictive of success in many endeavors, both professional and personal. In fact, grit predicts how well people complete many types of tasks more accurately than talent and I.Q. do.

During the event, participants were asked: “How much, between 0% and 100%, should you care about your employees?” One attendee answered that 100% is risky; what if you need to fire this person? Professor Kohlrieser explained that high- performing leaders care enormously– they care100% for their team members– however, they know where the boundaries to the caring need to be. Specifically, they know that their role is not to rescue people.

The importance of caring for others is frequently underestimated compared to other leadership traits. In truth, even top managers often fail because they are disconnected. They close their hearts, which leads to low trust in their working relationships and low engagement in the organizations they manage. Gallup studies show that employee disengagement is widespread in Europe and especially America. For individuals who do feel highly engaged at work, the same studies show that trust-based relationships play a central role.

A high capacity to form attachments and bond with others is one of the pillars of resilience. Strong personal bonds give us the confidence to take risks and aim for stretch goals. They are also vital in supporting us as we recover from failure and disappointment. Relationships based on trust are our “secure bases.” They form a network of people we know we can count on, both in our personal lives and at work.

The concept of a secure base goes beyond people. A secure base can also be a goal, a place or even an object that allows us to go out in the world, explore and experiment with confidence. The core function of a secure base is to provide protection and comfort as well as energy. For example, Nelson Mandela credits his grandmother for enabling him to learn from his prison experience. The poem Invictus by William Ernest Henley also constituted a secure base for Mandela– a powerful reminder that hardship and fear are no match for an unconquerable soul. Great managers draw strength from their secure bases, and they in turn become secure bases for others.

Coping with stress

How well leaders cope with stress helps to determine how resilient they are overall. Studies have shown that stress is not, in and of itself, physically harmful. Stress reactions such as a pounding heart and fast breathing prepare our bodies to meet a threat. They energize us to act. In fact, they are an integral part of the “fight or flight” response that has allowed humans to survive dangerous situations since the dawn of our species.

Good leaders need to experience a sense of urgency when their projects are at stake. Momentary stress can help galvanize individuals and teams at a critical juncture. In contrast, people who never worry about anything cannot get their organizations to perform at optimal levels. What is the right balance between too much worry and not enough worry? The constructive approach is to return as quickly as possible to a positive state. Chronic worry is the most destructive – it saps the joy of living.

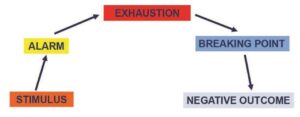

As a first step, it is useful to become aware of our stress levels (see Figure 1). How long does it take us to move out of a bad mood? Are we feeling exhausted or simply tired? Have we noticed a lowered resistance to infection or recurring migraine headaches? It is important that we heed our bodies’ distress signals. Two participants shared experiences of reaching their breaking point at work. One spoke about burnout and the other about a debilitating stress-related health issue. They both felt they had ignored their personal “alarm bells” when working under sustained pressure. One of the main lessons they extracted from their experiences is that obtaining results is important, but getting stressed does not increase effectiveness or productivity. Another lesson learned: when returning from stress leave, keep a sense of humor.

Figure 1: Stress response

Physical symptoms are one of the four areas in which stress manifests itself. Intellectual stress reactions include diminished creativity, cynicism and negative thinking. People who experience social stress reactions tend to stop seeing friends and returning phone calls. They progressively isolate themselves. Lastly, people who endure spiritual stress reactions lose a sense of meaning and purpose.

To enhance their resilience, leaders need to identify the coping mechanisms that allow them to relieve tension and regain their positive energy. These stress management options include “talking out” worries and concerns, doing something for others and healthful eating.

Stress management options

Awareness of stress responses

Take responsibility for stress responses

Create clear and specific goals

Modify destructive personality patterns

Physical exercise

Talk out worries, anxieties and concerns

Learn to let go – grieving what is gone

Avoid self-medication

Get enough rest

Balance work and recreation

Do something for others

Take one thing at a time – prioritze

Give in once in a while – flexibility

Learn relaxation – meditation, imagery, music, massage

Nutrition

Positive bonding – manage or stop negative relationships

Deal with emotions by awareness, expression and/or redirection

Learn to laugh

Make stress management part of a life-style and not just a technique

Find, use and understand the meaning and purpose of what you are doing.

Resilient Teams

Leaders also have a social and moral responsibility to consider the resilience of others. They must become attuned to the people around them and learn to recognize when a colleague is under a lot of stress. Does the person communicate a lack of meaning in their work? Does he or she exhibit negativity, over-victimization or continual anger? Social behaviors such as lateness and failing to come to meetings are also clues.

Managers who notice these signs need to reach out to the stressed person and engage in an honest discussion. Sometimes the best way to initiate the conversation is to ask a question: “Is everything all right? It appears you may be under a lot of stress. Is there anything I can do to help you?” The questions should be gentle and respectful.

Managers have a clear interest in working with vibrant and energetic employees. To avoid stress becoming a performance issue, leaders should take an active role in promoting resilience and boosting energy in their teams.

The Alexander Technique

Rosa Luisa Rossi, an instructor in the Alexander Technique, demonstrated to participants the benefit of improving posture and movement habits. Simple changes in breathing, posture and motion can relieve stress and tension. The way we hold our heads at the top of our spine, for example, tends to become an automatic and unconscious habit. However, since our heads weigh between fi and seven kilos, any imbalance has repercussions in several areas of the body. Over time, changing our habitual patterns of movement allows us to avoid pain and accumulated strain. This includes examining how we sit at our computer and how we walk. She concluded that resilience is the capacity to change rigid habits in both mind and body.

Positive Mindset

Cultivating a positive mind set is one of the keys to resilience. Despite our brain’s innate tendency to identify threats, we can consciously choose to strengthen certain thought patterns over others. It is as if we had a flashlight in our minds that we could shine in different directions. Our natural tendency is to use this flashlight to look for danger and pain. However, we can use our mind’s eye to refocus. In essence, positive and negative mindsets are malleable.

The human brain is immensely powerful and complex: it holds 100 billion neurons, and each neuron is capable of 10,000 connections. The plasticity of our brain allows us to build or prune neural circuits over our entire life spans. This means that as we learn and grow, we rewire our brains. Emotional bonding, active curiosity and deliberate practice are three essential ways to foster new neural connections. It is also worth noting that the best way to turn off our danger-seeking mental flashlight is to have a secure base.

Another reason that a positive mindset enhances resilience is that how we think about our stress affects how our bodies react to stress. Recent scientific studies have shown that people who experienced high stress in the previous year ran a sharply increased risk of dying only if they viewed stress as harmful to their health. Those who also reported high stress in the same time period but did not view their stress as harmful were at no greater risk of dying. In fact, they showed the lowest risk of death of anyone in the study(including those who reported low stress).

Embracing a positive mindset does not mean ignoring our feelings of grief. We must allow ourselves to grieve for what we’ve lost – colleagues, friends, projects, dreams. Understanding loss and failure are also fundamental to the recovery process. Setbacks are inevitable in life, and we must learn to welcome the lessons they yield. Extracting meaning from adversity allows us to move on.

Beyond resilience: The joy of living

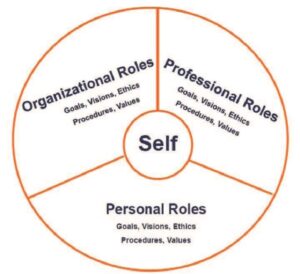

Building resilience is essential, but we must also remember that the end goal is to find joy in life. We wish not just to survive, but also to thrive. To this end, it is useful to examine the combination of our organizational roles, professional roles and personal roles to ensure that the different aspects of our identity are in balance and that we are able to experience the joy of living.

Figure 3: Identity and life roles

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD Nexus. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/nexus