More than 40 participants from around 20 companies attended a Discovery Event to learn about new ideas and frameworks on talent management, specifically those related to changing employee behavior. In a stimulating and open environment, they exchanged ideas, as well as sharing challenges and insights.

As anyone who has enthusiastically resolved to do more sport or stop smoking knows, it is hard to change one’s behavior in a sustained way. So, imagine how much Yet this is one of the main managerial roles: To help employees change their behavior, for both the employees’ and the company’s benefit. Managers can do so by building essential skills or encouraging direct reports to stop doing something or to do it better or differently.

According to an IMD global study of 500 executives, managers believe that only one in two attempts to change employee behavior is successful. Around a third know the techniques and are sure they can motivate their employees to change, but only one in ten managers knows how to do so in a sustained way. These results are not surprising, since managers tend to use limited tools to identify what needs to change and apply conventional tactics, such as advice, feedback or training, to resolve the issue. Rarely do they explore how to change. They also mostly underestimate the influence of the context – the environment and conditions in which behavioral change happen – on changing employee behavior and sustaining it.

How context influences behavior

It is well known that context and life circumstances – such as support from family and friends, the number and quality of social connections, external rules and culture – are vital for sustaining changed behavior. This has been proved in various settings. For example, more than half of prisoners relapse into criminal behavior if they are released into the old unchanged context. Similarly, brainwashed US veterans from the Korean war reverted to their old habits and behaviors once back home.

In a business setting, managers’ perceptions and attitudes are another important element of context. These are set within the first month, during which most managers instinctively divide their employees into those they can rely on and the rest, thus creating long-lasting psychological stereotypes of strong and weak performers (Table 1).

| Strong performers | Weak performers | |

| Manager’s

perception |

More motivated, proactive, innovative, big picture thinkers, better leaders, positive, agile and open-minded | More defensive, parochial, critical of innovation, prone to hoard information and disrespect authority, unlikely to go beyond the call of duty |

| Manager’s

behavior |

Explains “what and why,” open to their ideas, act as sparring partners, available, shares more, assigns more challenging tasks, more personal interest, invests in them | Tells “how,” pushes own ideas, monitors actions and results, focuses on KPIs, less patient, more directive, less delegation |

This psychological stereotyping causes different approaches and attitudes when dealing with strong vs. weak performers, thus reinforcing their behavior. When leaders have higher expectations, this increases direct reports’ motivation and effort and improves performance. In psychology, this is known as the Pygmalion effect.

Conversely, managers’ negative expectations set their employees up to fail: Bosses assign routine tasks with little scope for employees to take charge; they monitor more closely and micro-manage, thus conveying lack of trust. Employees lose confidence and feel less inclined to take risks or come up with ideas; a downward spiral begins.1 The single most influential factor in a person’s working context is their relationship with their manager, so changing the context means managers doing something differently.

Change levers

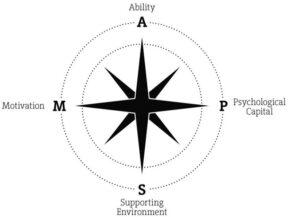

In order to achieve sustained change in employees’ behavior and help them perform and develop effectively, it is not enough for managers to change their own attitude towards their subordinates. They should also use the key levers summarized in the MAPS model2 motivation, ability, psychological capital and supporting environment (Figure 1).

Figure 1: MAPS model of key behavior change levers

Figure 1: MAPS model of key behavior change levers

Most managers tend to focus on ability, underestimating the importance of the other three. We will therefore concentrate on the three undervalued levers.

Instilling motivation

Motivation gets people inspired, proactive and involved. When people are motivated to achieve and sustain a specific change, they are far more likely to succeed, as higher motivation means higher effort.

There are two types of motivation. Most managers are aware of the importance of intrinsic motivation, but mostly they focus on extrinsic motivation, such as awarding bonuses and merit increases. The latter are effective in boosting performance on those tasks that use mechanical skills. For cognitive skills, intrinsic motivation is far more effective.

The latter are effective in boosting performance on tasks that use mechanical skills. For cognitive skills, intrinsic motivation is far more effective.

Intrinsic motivation is fueled by internal feelings – the fact we find something fulfilling or enjoyable. According to self-determination theory, intrinsic motivation includes the following three factors:

- Autonomy: the sense of being in control and having a choice. When given more autonomy, people are more likely to put in sustained effort, perform better, fulfill goals, achieve even assigned changes and experience enjoyment and satisfaction. To increase a sense of autonomy, managers should involve people, get the tone right and offer choices.

- Mastery: the sense of being competent and relishing challenge. People are more motivated if they feel competent, especially for complex and broad goals. Besides, challenging and difficult goals lead to higher job satisfaction and feelings of success. Reminding an employee of their strengths is a good way to increase a sense of mastery. Positioning things as a challenge, rather than change, and appealing to their pride is also effective.

- Connection: the sense of being meaningfully connected to other people and what you are doing. Having a sense of purpose leads to higher performance, enjoyment and satisfaction, and sustained dedication. Managers can boost connection by involving people – asking why it matters and what the benefits of change will be; explaining the reasons for change; and making it personal and practical.

Remember: One size does not fit all – people’s intrinsic motivation, as well as advice on increasing it, depends heavily on gender, culture, age and career concept.3 The latter categorizes how people see their own career path: Are they experts, or following a linear, spiral or transitory track? Managers cannot apply the same challenges and goals to everyone to achieve optimum motivation.

Developing psychological capital

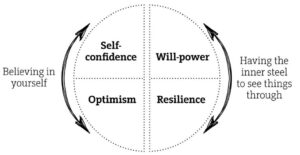

Psychological capital refers to the crucial inner resources a person needs to thrive and succeed at almost everything. In other words, success in changing employees’ behavior depends on their own self-belief, as well as the willpower and resilience to see things through and sustain change.

Employees’ psychological capital affects a wide range of work-related outcomes, such as job performance, work satisfaction, citizenship, absenteeism and stress. Personality and self-esteem are crucial parts of psychological capital, which managers can significantly strengthen through support and creating the right work environment.

The four elements of psychological capital are self-confidence, optimism, willpower and resilience (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The four elements of psychological capital

Self-confidence refers to one’s belief and level of trust in oneself and one’s abilities. Confident people are more likely to work hard and keep going; achieve behavior change; react positively to training; and learn practical and complex interpersonal skills.

Self-confidence is directly related to internal locus of control – when something goes well, a person believes it is because they have done well, rather than attributing their success to pure luck or to others, as those with an external locus of control tend to do. Building self-confidence means increasing internal locus of control, which makes behavior change last longer.

Managers can help their subordinates build confidence in several ways, through:

- Guided mastery, helping them achieve success by, for example, ensuring they understand what they need to do, by planning with them how they will practice a new behavior, and highlighting progress and praising them for it.

- Wisely identifying a role model, not to showcase perfection but to illustrate that progress is achievable. The role model should be reliable and easy to relate to (e.g. same gender, ethnicity, age).

- Persuasion using the Pygmalion effect, i.e. expressing confidence in their abilities, reminding them of their strengths, publicizing achievements.

- Physiology. It is possible to reduce anxiety and stress via deep breathing, mindfulness or high-power poses.

Optimism is a mindset that focuses on positive thinking, taking credit for good events and viewing bad events as temporary. Pessimists tend to over-generalize, personalize and have an “all or nothing” attitude. Optimists cope better with setbacks and are more likely to sustain change, yet there is a danger that they might underestimate risks and not prepare enough for setbacks.

The best way a manager can help increase employees’ optimism is by reinforcing their true self-concept, helping them frame things positively – “I messed up that presentation” rather than “I’m useless, I never present well.”

Willpower is the capacity to exercise self-control, to start, continue or stop doing something. Willpower can be built by encouraging people to look after themselves (enough sleep, healthy eating, less stress), to practice simple self-discipline (keeping a diary, good posture, developing the non-dominant hand) and to stop distractions and build focus (via positive, motivational or instructional self-talk and mindfulness).

Resilience is the ability to cope with adversity and grow stronger, to develop alternative ways of doing things when faced with difficulties and failures. Resilience in the workplace can be built in three ways by:

- Promoting a growth mindset by praising people for hard work and improvement; asking what they learned; and pointing out fixed-mind tendencies.

- Cultivating self-compassion by comforting people, helping them depersonalize the issue and be more objective about themselves, rather than being totally driven by perfectionism. Resilience without self-compassion is much more fragile.

- Planning for setbacks by identifying problems that might arise with the desired behavior change, and how to respond to each one – what are the options, how effective is each likely to be?

Together, willpower and resilience provide the inner steel, or grit, to see things through.

Building a supportive environment for behavioral change

The final element in the MAPS model for sustaining changed employee behavior is creating a supportive environment at work in terms of physical environment, team dynamics and organizational culture. A supportive environment can be built with three levers – social support, habit structure and choice architecture. The first two are not largely influenced by managers, whereas the last one is easily controllable and more efficient in terms of helping employees change their behavior.

The art and science of choice architecture is based on nudges – a term that comes from behavioral economics, referring to a feature of the environment that influences the choices people unconsciously make, without coercing them. Managers can influence employees’ behavior by paying attention to the following five nudges:

- Information framing. The same fact can be presented in ways that will lead to different reactions (“1 in 10 people die five years after surgery” vs. “9 in 10 people are alive five years after surgery”). Experts, more confident people and those who are close to achieving their goal respond best to criticism, whereas beginners and unconfident people react better to praise and positive comments.

- Priming is widely used in different areas and settings. Priming commitment can be achieved by having employees sign their development plans. Priming openness can be achieved by using more comfortable chairs, whereas harder chairs lead to tougher positions in negotiations. Priming confidence can easily be achieved by using more positive words in conversation or written feedback.

- Loss avoidance. People are more motivated by the thought of losing something than of receiving a reward. Losses are perceived as around 2.5 times more powerful than gains, so instead of promising gains set the goal to avoid losses. For example, give a prize upfront and say the person can keep it if certain conditions are fulfilled.

- Decision economics is simple: In order for change to happen, the costs and benefits of the change should add up and be clearly communicated.

- Social influence. Making people aware of social norms (desired or actual) changes their behavior (especially telling them in as personal and meaningful a way as possible, for instance “most of your colleagues do…”). As people care about their reputation, peer pressure and accountability can also help to influence – for example, by making a development goal public or creating visibility on performance levels.

Key learnings for managers

- The right context is one of the most important yet undervalued factors in sustaining behavior change. Managers can bring out the best in people by paying more attention to the recruitment process and making relationship a priority during onboarding.

- Be careful with labels, including inherited labels, as they can create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Managers should solidify their own opinion about their direct reports and be careful about intuitively deciding on high vs. low performers.

- Hold positive expectations about employee performance, since in most cases this helps them deliver more.

- The MAPS model – motivation, abilities, psychological capital and social environment – provides a systematic approach to changing employee behavior sustainably.

- Appealing to individual preferences for autonomy, mastery or connection can increase intrinsic motivation, which is vital for sustaining behavior change.

Managers can strengthen employees’ psychological capital – self-belief and grit – by support and the type of work environment they create, which includes physical environment, team dynamics and organizational culture. - Tackle problems as they emerge, by asking not telling – “How do you think the presentation went?”

- Actively nudging employees to manage their choices is gaining traction.

1- Manzoni, J.F. and J.L. Barsoux. The Set-Up-To-Fail Syndrome: How Good Managers Cause Great People to Fail. Boston MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

2- Kinley, N. and S. Ben-Hur. Changing Employee Behavior: A Practical Guide for Managers. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

3- Driver, M.J. “Career Concepts and Career Management in Organizations.” Behavioral Problems in Organizations, 1979: 79-139.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD’s Corporate Learning Network. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/cln