IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Technology

The global chip shortage: Rescue must come from outside

These are the latest rankings in the technology industry.

Click on the company’s name to see details of the score.

Intel didn’t rank well. The implication at national level is a dangerous lack of involvement by the strongest technology companies. Whether they’re partnerships or joint investments, they are absent at the moment. It’s hard to imagine Intel alone can turn the tide; it’s too much to ask of a single company.

Now you’ve seen the ranking. Explore our professor-led programs to become future-ready yourself.

Now, you may be curious how other US chipmakers are doing. Aren’t AMD, Nvidia, and Qualcomm prime examples of innovation powerhouses? Haven’t they led the latest hardware advancements in areas such as AI, mobile, or video gaming?

The answer is a resounding yes. But they’ve done so by ignoring the manufacturing aspect. They all rely heavily on Taiwan’s TSMC to manufacture their leading-edge products. And because they don’t have factories or fabs, they don’t inherit any sunk cost. They are asset-light compared with Intel and can therefore afford to be agile.

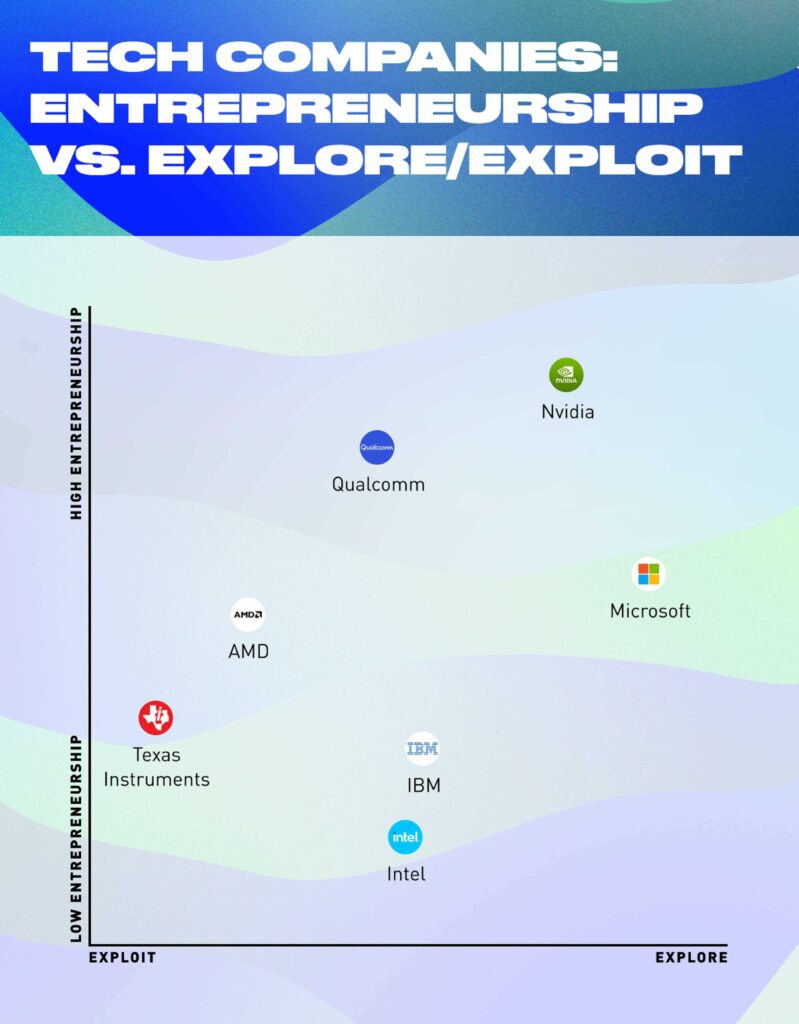

The chart below shows us these exact dynamics. Similar to other industries in our analysis, we fed our algorithm with 10 years of business publications, including the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Financial Times, and other standard-bearing business publications. We also included corporate press releases. This enables us to characterize how companies have behaved based on what’s been reported over long periods. You can take a look at how we built this algorithm here.

The Y-axis displays the level of entrepreneurship; defined as a company’s success when it branches out from its core business. You can see how Intel got stuck making microprocessors for PCs. Meanwhile, Nvidia has moved on from deploying graphic processors only in the gaming sector; it’s now leading in designing chipsets for AI applications. Qualcomm has become the undisputed leader in mobile. AMD, which used to be an underdog on the brink of bankruptcy in 2014, now provides the industry with the most powerful gaming processors.

It’s therefore not an understatement that technology companies are the fruit flies of the modern economy. The velocity of the sector is swift, and executives must pivot fast to avoid being left behind. As we can see on the X-axis, some companies are geared toward exploiting near-term opportunities; others are far more explorative, willing to acquire new capabilities and wade into the unknown.

Intel’s conservatism is understandable; it is the only player in the semiconductor sector that has an enormous footprint of factories, but with that comes the baggage of risk avoidance. It can’t branch out into new businesses without the worry that its factories might stand idle. Asset-heavy companies are always more conservative and, paradoxically, when others are asset-light and you are not, you end up being disadvantaged.

All this makes sense at the company level, but doesn’t add up at the national level. The West has long shunned semiconductor production, focusing instead on sales and design. Because of the required investment of capital, investors nudged companies to outsource these low-value-added activities to Asia. The richest part of the world can’t spend on manufacturing capacity, because their companies must make even more money than everyone else.

The question we must ask is this: If an American firm were to step in, who would have the largest balance sheet and ability to solve hard problems? Let’s take a bold risk and single out Microsoft. It’s in great shape, but more importantly, it has achieved its own turnaround previously.

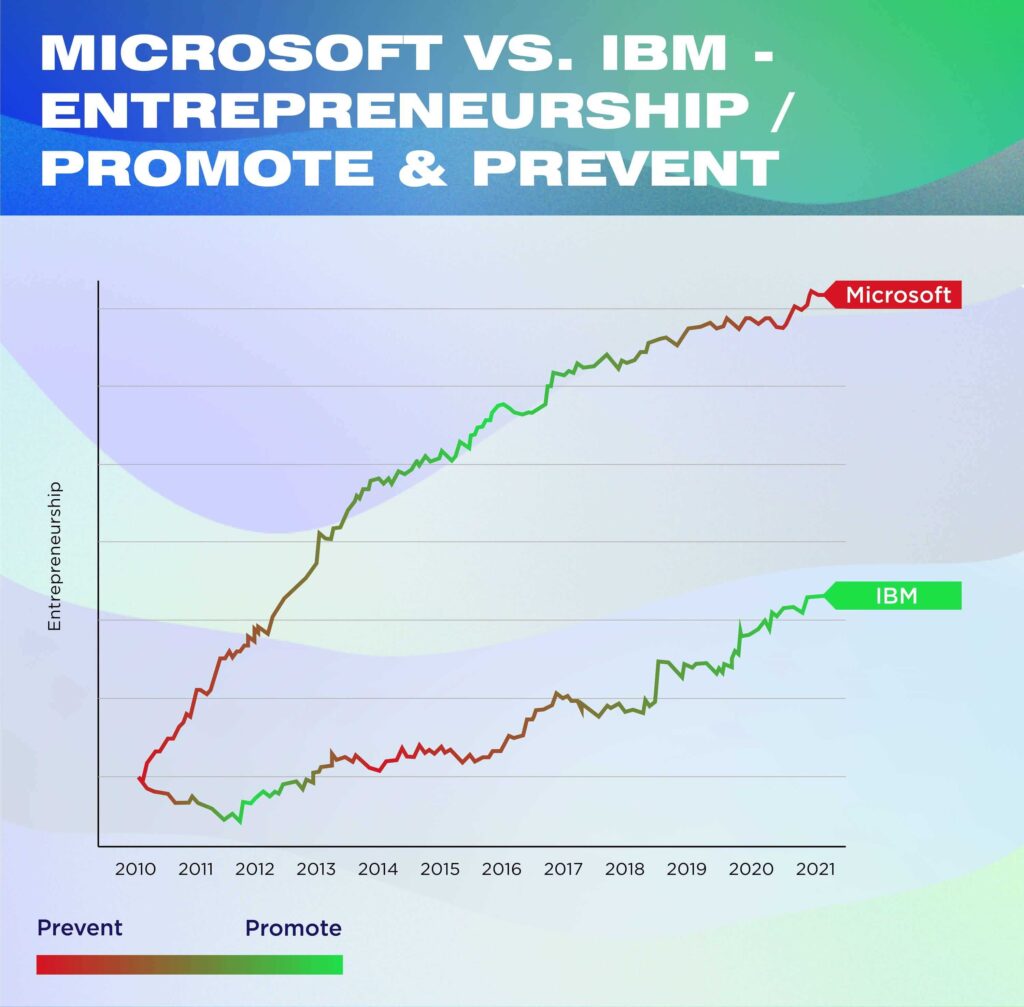

In our readiness indicator, many tech giants harbor enormous resources, but Microsoft has lived through a near-death experience and is now at the apex of its valuation. When CEO Satya Nadella took over, the transition toward Office 365 as a subscription model was perilous. The hardware business had been going nowhere; Microsoft was still making money on the PC market, but that was not growing. All it had was Azure, but it wasn’t clear that the cloud computing service would become the second-best competitor against Amazon’s AWS. IBM Watson at the time looked equally if not more promising.

The chart below shows how Microsoft won the day. It kept its entrepreneurial spirit high, but with an unfailingly realistic assessment. It doesn’t just promote a rosy future, it doesn’t preach a technological utopia, it doesn’t even promise boldly to change the world. Rather, its executives try their best to minimize catastrophe as the company scales all its new businesses, including cloud computing, augmented reality, and its own line of tablets. Microsoft has a healthy paranoia about what could go wrong, but thart doesn’t stop it from trying new things. What Nadella calls the growth mindset is what turned the company around.

And in a hard science such as semiconductor manufacturing, you need exactly this kind of sober optimism, deep expertise, and even deeper pockets. Is this too far-fetched? Microsoft has already been toying with the idea in its own blog. Maybe they are ready to play the hard game.